Initially, most Nebraska politicians were cautious about voicing their opinions of Sen. McCarthy. However, in 1952, former Nebraska Governor Dwight Griswold said it was a "thrilling experience" to hear McCarthy speak in Chicago. He was particularly impressed when Senator McCarthy said,

"There is no such thing as being a little disloyal." McCarthy’s ideas, if not his attacking style, hit a nerve, and legislative bodies tried to respond to the perceived threat.

The Nebraska Unicameral was one of the bodies that tried to do something about communism. In 1961, the Nebraska Judiciary Committee approved LB723, a proposal to outlaw the Communist Party in Nebraska. The bill stated that membership in any party advocating the overthrow of the government was a seditious (rebellious) act against the state. Anyone who was convicted was barred from any state job or "position of trust" on any level. The debate over the proposed ban was heated. Supporters argued that it was obvious that communists wanted to dominate America. One Senator from Arapaho said,

"If ever there was a time when America should rise up it is now. You can’t expect to meet this enemy in the open. They only operate through destructive underground channels. They are headed for your home and your town."

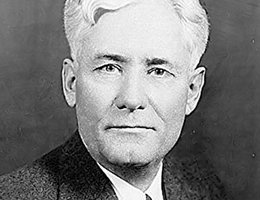

Nationally, in 1950, Nebraska Sen. Kenneth Wherry — who was the leader of Senate Republicans from 1949 to 1951 — and Sen. Hugh Butler supported McCarthy. Much of their support was in response to years of frustration under the Democratic administrations of President Roosevelt. For McCarthy and others like Sen. Butler, the New Deal’s mildly radical reforms, administered by Ivy League graduates, were tantamount to treason. In 1950, Butler lashed out at Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson:

"I look at that fellow, I watch his smart-aleck manner and his British clothes and that New Dealism in everything he says and does, and I want to shout, ‘Get out! Get out! You stand for everything that has been wrong in the United States for years!’ "

In the following years, both Nebraska Senators (and even one of their successors, Dwight Griswold) died in office.

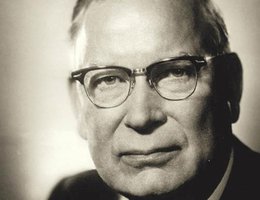

By 1954, the press and television reporters were questioning McCarthy’s claims of communist infiltration. Edward R. Murrow and CBS TV broadcast a program composed almost entirely of McCarthy’s own words and pictures. It showed the Senator browbeating witnesses and never producing evidence. It was a damning portrait of a fanatic. Many Senators were also tired of McCarthy’s unsupported allegations, and a resolution was introduced in the Senate to reprimand him. The vote was lopsided — 65 senators voted to censure McCarthy, and only 22 voted against the measure. Senators serving from Nebraska in 1954 split on the vote. Roman Hruska voted against the censure, while his fellow Republican Hazel Abel supported it.