Former Nebraska Gov. Val Peterson was head of the Federal Civil Defense Administration when he warned citizens against the dangers of massive fallout from the hydrogen bomb.

In the 1950s and 60s, Nebraska was the target of Russian nuclear bombs. With SAC on our eastern border, airbases and missile bases across the state and a major ammunition dump outside of Hastings, the state would be "Ground Zero" — the aiming point — of nuclear missiles and bombers in the event of a nuclear war. The problem for civilian and military officials was how to devise plans that would give civilians a chance to survive a nuclear war.

There had been civil defense agencies in WWI and WWII, but what made "CD" different in the 50s was the atomic bomb. The potential devastation was so great and people were so nervous that old approaches wouldn’t work.

By 1950, the first CD plans called for citizens "duck and cover" if they saw a bright flash of light from an atomic bomb explosion. The idea was that if an atomic bomb exploded, you would try to survive the first blast and then look for shelter from the radiation for a short time. Public and commercial buildings that were built strongly and had room for groups of people were set up as shelters with food, water and cots. They sported distinctive "CD Shelter" signs. Citizens were told to learn the locations of shelters in their communities.

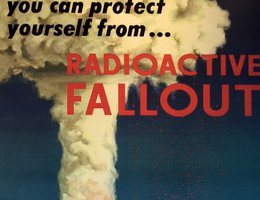

But then, in 1954, the U.S. tested their first "Superbomb", a hydrogen fusion bomb that was 500 times more powerful than the Nagasaki bomb. Scientists were surprised when debris from the bomb that had become radioactive began to fall out of the sky 72 miles away from the blast site. The blast area itself and the area that was exposed to radiation strong enough to sicken and kill humans were much larger areas than they had expected.

Nebraska Gov. Val Peterson was serving as the head of the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) when the reports came in. Peterson recognized that the Soviets would also develop the Superbomb and that the blast destruction and fallout would be much more deadly than they had thought before. The scientists presented maps with huge elliptical shapes on them showing how far downwind the radioactive fallout traveled:

"The ellipses stunned civil defense planners. By a major shift in policy they had replaced previous ‘duck-and-cover’ or ‘stay put’ planning by a policy of pre-attack evacuation which dispersed metropolitan populations beyond the inner circles of near-total and heavy blast damage. Gov. Val Peterson, as head of FCDA, made the policy switch once he took a good hard look at the blast and heat effects. . . . Gov. Peterson recognized that too much of America’s metropolitan population resided inside the 14 mile radius of the superbomb’s punch. It was sheer suicide, he reasoned, to put 35 million Americans in the sitting duck category. This is the simple background for the policy of evacuation which is now being implemented." — Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist 10, Nov. 1954, 349-5.

So, the FCDA asked states and local authorities to develop plans to move everyone out of the target areas if an atomic war started. At that time, A-bombs were only carried on airplanes and with a system of Distance Early Warning radar sites across Canada (the DEW line) planners assumed they would have at least four hours to evacuate the people. Nebraska and the other states developed their plans. The Nebraska Survival Project admitted that "no effective shelter now exists in the target areas, and evacuation to safer areas is the only alternative remaining." The plans, published in 1958 and updated in 1961, included maps detailing evacuation routes, and named Columbus as the new capital of Nebraska in the event of Lincoln’s destruction.

Officials practiced the plans. In July of 1957, mock A-bombs were dropped on 100 American cities to prepare Civil Defense agencies with an emergency situation. Mock bombs were dropped on Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, and Sidney. Area cities were warned of fallout possibilities. Boy Scouts of the Cornhusker Council in Nebraska were prepared along with scouts from all over the country to work with Civil Defense in case of an emergency. Scouts were to search for lost persons, administer first aid, protect animals, and rescue people.

A similar nationwide Civil Defense exercise was held in 1959 when five bombs were dropped in Nebraska. One was a "surface blast" at the Sioux Ordnance Depot. Later an alarm system was installed which would become operational in the event an actual attack did occur. Other bombs were dropped at Grand Island and Offutt Air Force Base, and Omaha.

But then, missiles reduced the warning time from hours to just minutes.

It became obvious to almost everyone that it would be impossible to evacuate entire cities in only 15 minutes. So the emphasis went back to shelters.

By 1964, the Lincoln metropolitan area had public shelters for 100,000 people. If they survived the first blast and wave of radiation, people could survive in fallout shelters for weeks on the food, water, and supplies that were kept in shelters. In Nebraska, the Department of Agriculture created the "Nebraskit" a compressed biscuit made from wheat, corn or milo. Milk bars were also made from dairy products. Each of the Nebraskits were designed to satisfy a person’s food needs during a stay in a fallout shelter. According to an enthusiastic state newsletter from the time, "The rations have a long shelf life, are ready to eat and are palatable to all age groups." Other varieties were produced later. Cartons of Nebraskits were stored in fallout shelters throughout the United States.

Although public shelters are now used more for severe weather situations, many of these shelter signs can still be seen on buildings today.