The change in the Nebraska landscape was dramatic. In just a few short years, cattle replaced the American bison as the leading, cloven-hoofed, grass-eating mammal on the Great Plains. In 1850, millions of bison ranged the grasslands and were the main natural resource for the region’s American Indians.

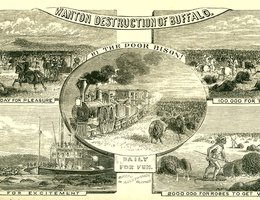

In 1868, the steel rails of the transcontinental railroad created a barrier that bison did not like to cross. That divided the great herd into northern and southern herds.

When the great trail drives began, bison interacted with the cattle being driven from Texas.

"Buffaloes travel in a straight line. When they were moving and encountered a herd of Texas cattle they invariably bored right through the herd, turning neither to right nor left. It was just the same if but one or a dozen buffaloes were on the move — they walked straight through." –James H. Cook as told to Eli S. Ricker, May 23, 1907

The cattle infected the bison with new diseases: the dangerous brucellosis as well as Texas tick fever, which dramatically weakened the bison herds.

Then in 1870, a process was developed that so bison hides could be commercially tanned into soft, flexible leather. This happened at the same time there was a high demand for leather to make the belts that powered machines in the Industrial Revolution. There were huge markets in England, France, and Germany. Bison hunters poured onto the Great Plains. By 1880, the combination of disease, environmental stress, and hunting left the bison near extinction.

The destruction of the bison had two important consequences: