When homesteaders arrived on the Great Plains, they found a challenging environment where survival was the goal. The native tribal people had been meeting these same challenges for thousands of years and had evolved complex economic, agricultural and cultural methods of coping. What was life like for the Native Americans in the mid- to late-1800s on the Great Plains?

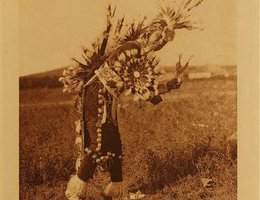

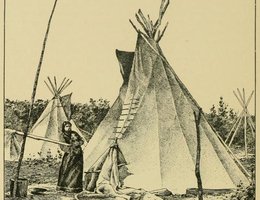

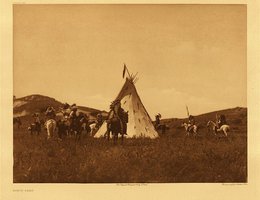

By the mid-1800s, the Pawnee, Omaha, Oto-Missouria, Ponca, Lakota (Sioux), and Cheyenne were the main plains tribes living in the Nebraska Territory. Each tribe faced the challenges of the plains in slightly different ways. Some tribes had settled into their own villages with earth lodges for shelter. These tribes were primarily engaged in farming, with seasonal buffalo hunts to supplement their diets. Other tribes were much more nomadic, especially after they got horses. They lived in the 1850s equivalent of mobile homes — tepees. These tribes were hunters.

Plains tribes can be loosely divided into those who had settled in villages and farmed and the nomadic tribes who roamed across the vast plains hunting for game. Most of the farming tribes also went out of their villages every year to hunt buffalo. Both groups used tepees when they were on the hunt, but the nomadic tribes concentrated more on training horses than building earth lodges.

In Nebraska, the Pawnee, the Omaha and the Oto-Missouri were tribes who had discovered how to farm and build lodges out of the soil around them.

The Pawnee were the largest tribe in Nebraska and lived in the area longer than any other group. The earliest known villages of the Pawnee had circular earth lodges located along the lower Loup River where most of the tribe continued to live even after contact with Euro-Americans. There were also villages along the central Platte and Republican Rivers.

It was estimated there were ten to twelve thousand Pawnee in the early 1800s.

Because of their numbers, the Pawnee had little to fear from their enemies, but in the early 1800s their lives began to change. Smallpox and other diseases for which they had no immunity caused the deaths of about half of their people. By the 1830s, villages on the Loup River were being raided by the nomadic and better-armed Lakota (Sioux). In the 1850s the Pawnee moved eastward along the Platte River to avoid the attacks, and this put them in contact with the new immigrants.

The Omaha lived in southeastern South Dakota when first mentioned in historical records in the early 1700s. Near the end of the century they were in Thurston County. They lived in villages of earth lodges; raised corn, beans, and squash; and went on summer and winter buffalo hunts in western Nebraska. At one point the Omaha had a population of nearly 10,000 members.

If you were an Omaha Indian in the 1800s, your dinner may have been corn soup, vegetables and either fresh or dried buffalo. Later, their contacts with fur traders and immigrants introduced them to wheat and metal cookware, and "fry bread" became a popular food.

After Nebraska became a territory, the Omaha settled on a reservation in Thurston County.

The Missouria were a large tribe, but early contacts with fur traders brought diseases for which they had no immunity. Small pox, whooping cough, and other new illnesses nearly destroyed them. By 1800 there may have been no more than one hundred people in the tribe. For protection they joined the Oto who had moved out of Iowa and were living in an earth lodge village on the Platte River not far from where it joins the Missouri. Like the Pawnee they grew corn, beans, and squash and went on biannual buffalo hunts.

By 1800, what became South Dakota was labeled as "Lakota land" on maps, even though they had been pushed onto the Plains during the 1700s. There were thousands of Lakota. They began raiding Pawnee villages in central Nebraska in the 1830s. The Lakota were also fighting with the Crow on the buffalo range in eastern Wyoming.

The Lakota were the master hunters of the region. Next to corn, bison meat was the main food for the Lakota. One bison provided enough meat to feed one person for one year. But by the 1800s, the Lakota were also hunting bison to sell hides to European traders.

The Ponca faced difficult times in the 1800’s. In the 1820s, they had a risky partnership with the Brulé Lakota. The Ponca abandoned their villages and tried nomadic buffalo hunting. The partnership and the experiment both failed. In 1858, they settled on a reservation in what would become Boyd County. The Lakota began to attack them more violently, and nearly a fourth of the Ponca died trying to defend themselves.

By 1800, the Cheyenne had obtained horses and abandoned village life to become buffalo hunters on the plains of Wyoming. Here the tribe divided. Part of the Cheyenne continued southward into Colorado. The Northern Cheyenne, who remained behind, fought to keep the whites out of their new homeland. After 1850, they made several raids along the Overland Trail well into eastern Nebraska. In 1877, the Northern Cheyenne surrendered to the U.S. Army and were forced to join the Southern Cheyenne on a reservation in Oklahoma.