What’s for Lunch? What were meal times like on the frontier?

The light meal homesteaders’ children carried to school was called “lunch.” They ate lots of sandwiches, but what kind of sandwiches? They might have had cornbread and syrup, or bread and lard, maybe with a little sugar, or bread and bacon. It was a special treat to have a sandwich with meat in it. There were no peanut butter and jelly sandwiches — peanut butter wasn’t made in the 1890s.

Water was the usual drink with lunch. Schools had no refrigerators, so there was no cold milk. Students drank from a dipper out of a bucket of water. The bucket had to be carried from the closest well. If the school had a pump outside, children took turns pumping water.

There were no plastic lunch boxes or thermoses on the homestead. This girl is carrying her lunch in a tin container called a lunch pail. Some families could afford to buy lunch pails for their children. Others saved empty lard or syrup buckets to use as lunch pails.

For the adults at home, the noontime meal was often the biggest of the day and was called "dinner," not lunch. Corn in some form was usually on the homesteader’s table. Like now, corn was a large part of Nebraska’s agricultural economy, and there was at least one “Corn Girl” crowned in Kearney around 1907. Much of the food was home grown. Vegetables were grown in gardens and stored in root cellars. Fruits were dried. Cows would provide milk, cream and home churned butter. "Staples" like flour and cornmeal were bought or ground at a local gristmill.

Meat was a special treat. There was no refrigeration and meat had to be smoked, salted, or dried to keep it from spoiling. Pork was the preferred meat up until the early 1890s, as it could be smoked, salted and dried easily. Drying was also the most common method of preserving food grown in the garden.

In this photograph, the Hoffaker family, in east Custer County, appears to have brought the frame for a rope bed outside and set it up to dry food.

William McDonald was born in 1861 near North Platte, Nebraska, and he remembered "jerked" meat — meat that had been either smoked or dried.

"We used to have jerked buffalo, dried meat that a man put in his pocket and could chew on all afternoon. It was good and it was strengthening. A piece of meat 3/4 inch wide and 4 or 5 inches wide would be put out for drying. It dried as hard as sole leather and dark colored. If it was an old bull buffalo it made some real chewing. It was tough."

Agricultural products were symbols of the bounty of the land for many of the settlers. Check out common recipes from this era.

Watermelons were a delicacy for Nebraska settlers. When the watermelons were in season and ripe, they were a summer treat and a standard for the ten o’clock and three o’clock lunch. Some pioneer families even claimed to keep melons through the winter by stuffing them in haystacks.

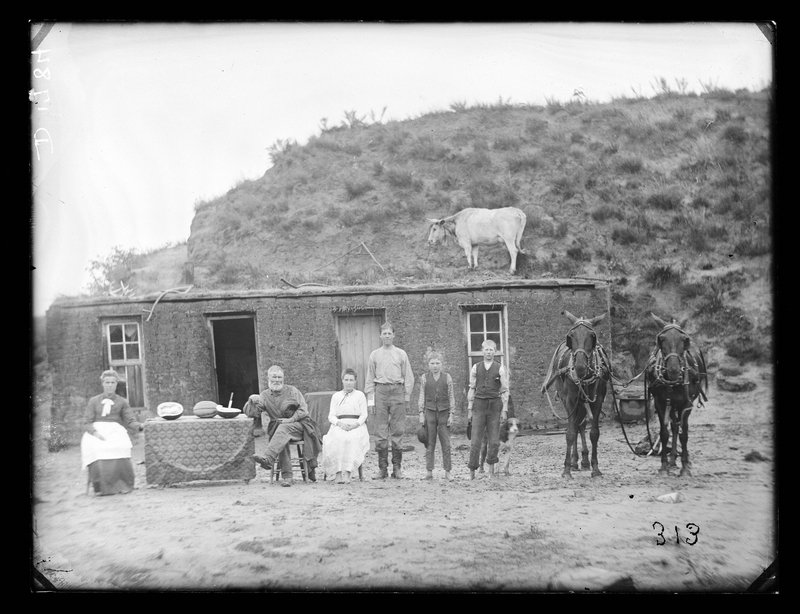

In photographs of sod house families, watermelons are often seen as symbols of the bounty of the land. The Kem family posed for this photograph with their watermelons in the 1880s. Many years of good crops made the settlers confident, and although many hard years followed, the settlers remembered "the remarkable crop of watermelons they raised that first Nebraska summer" for the rest of their lives.

When Mrs. W. L. Downing wrote to the Nebraska Farmer in the 1970s, she reminisced about her first year living with her new husband in a sod house north of Stapleton, Nebraska. While her husband planted corn, Mrs. Downing "planted watermelons with a hand planter...Oh, those melons!" She remembered, "We had melons for everyone in the neighborhood."

How would the contents of the lunch you take to school differ from the contents of lunch taken by pioneer children?

Read the recipe on how to cook rabbit. Ask you parents if they have ever eaten rabbit.

Why are people living in Nebraska less likely to eat rabbit today?

Read the recipe for poverty cake. Why do you think it was given that label?

Sylvester Rawding brought his family to Nebraska in the 1880s. In 1886, they brought their lunch outside on a muddy day so that photographer Solomon Butcher could capture the family on film. Sylvester was a Union Army Civil War veteran, wounded during a skirmish near Mobile, Alabama. He was struck over the right eye by a musket ball that was never removed.

See if you can find the following things:

What is the family having for lunch?

Take a look at the feet of each family member. Why do you suppose daughter Bessie has clean feet? How did she keep them clean?

Is the cow standing on the roof of this dugout soddy?

Use the Photograph Analysis Worksheet from the National Archives to help you analyze the photo.