City and state officials began asking for federal troops to come to Omaha while the riot was still building — as early as 6:20 p.m. on the evening of September 28th, more than four hours before Brown was killed. But, because the requests were directed to both local Army posts, Fort Crook and Fort Omaha, and to the War Department in Washington, the signals were confusing. The Army intervention proceeded slowly at all levels.

Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Wuest, commander of Fort Omaha, was aware of the threatening crowd as early as 5:30 p.m., but he was unwilling to damage his career by intervening in a civil disorder without an explicit order. He was also unsure whether or not it was legal to use troops in a civil disorder.

So, local authorities needed to get a specific request for help from civilian officials and a command from higher up. Omaha officials tried to contact the governor, Samuel R. McKelvie, but he was in North Platte and unreachable. President Wilson had suffered a stroke and was unavailable. Finally, they reached Lt. Gov. P. A. Burrows. Burrows made the request for troops, and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker responded. He ordered Wuest to intervene.

By the time Wuest and troops from Fort Omaha did respond, city police were helpless. It was 9:30 p.m. when troops began to move, and Will Brown was about to be lynched before they got to the courthouse.

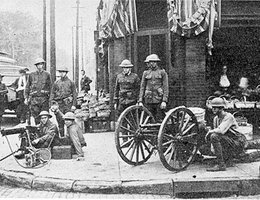

When they finally arrived, troops were stationed near the courthouse. But the mob had already departed, dragging Brown’s body behind them. Another company of troops was dispatched to 24th and Lake Streets, in the heart of the black community. They were there to prevent any further murders of black citizens. Orders were issued that any citizen with a gun faced immediate arrest. All blacks were ordered to remain indoors. By nightfall the next day, September 29, the Army could report that Omaha was quiet.

Meanwhile Major General Leonard Wood, Wuest’s commander, returned to Omaha on September 30 and assumed overall command. Troops were concentrated at 24th and Lake Streets, at the courthouse, and at 24th and O streets in South Omaha where many of the rioters had come from. Gen. Wood took command away from civil officials in order to rebuild the law enforcement agencies of Omaha to prevent any more violence. He also began an investigation of the riot. The Army began to arrest mob ringleaders on the basis of photographs confiscated from the public. Gen. Wood personally interviewed several suspected mob participants.

Even though photographs identified members of the mob, all of the suspects were eventually released.

After the riot, some wondered if more aggressive action by Colonel Wuest could have prevented the mob from murdering Brown, attempting to murder Mayor Smith, and destroying the courthouse. The Army succeeded in preventing further bloodshed and destruction in Omaha, but more timely intervention might have prevented the violence altogether. The city turned to figuring out who was to blame.