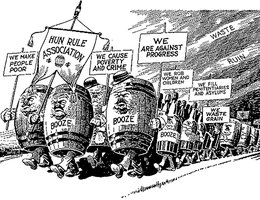

Prohibition of alcoholic beverages, like women’s suffrage, was a very emotional issue for most Nebraskans. Some saw an evil combination of saloons and alcohol and blamed liquor for a host of society’s ills. Drunken husbands spent their money on alcohol, money that would never benefit the family or community.

On the other hand, there were a number of large brewery and liquor businesses in Nebraska. And several ethnic groups that accepted alcohol as part of their culture and saw prohibition as a threat to traditional values. German-Americans, for instance, made up over half of the state’s foreign-born population and 23 percent of the overall population in 1910. A significant number of them were opposed to prohibition. The German-American coalition organized to oppose both prohibition and suffrage. Rhetoric on both sides of the question was heated.

"We fail to discover any reason why the liquor traffic should be legalized any more than any other known blight, contagion or disorder. As to prohibiting the traffic entirely, of course that is not possible; but it can be made an outlaw from society and driven as a criminal into hiding. [We must decide] whether the sale of liquors will be prohibited in this state, under an amendment to the constitution, or whether the saloon is to continue its licensed work of destruction."

— from Prohibition Party speeches, 1890.

"Out of due respect for the dignity of the individual, even — or especially — in a democratic society, the majority must refrain from imposing its almighty will on the minority, and it must never attempt by majority vote to regulate or legislate on questions what we eat and drink, how we dress, what books we read, how we spend our leisure time, and in what kind of schools we send our children."

— Republican Congressman from St. Louis, Richard Bartholdt, in an address to the German-American Teachers Association in 1909.

"Nebraska will be a state where the schoolhouse and the home are given precedence over the man traps created by a licensed whiskey traffic."

— from Prohibition Party speeches, 1890.

CHORUS

"I’ve got the blues

I’ve got the blues,

I’ve got the alcoholic blues.

No more beer my heart to cheer;

Good-bye whiskey, you used to make me frisky.

So long highball, so long gin.

Oh, tell me when you comin’ back again?

Blues, I’ve got the blues

Since they amputated my booze.

Lordy, Lordy, war is well,

You know, I don’t have to tell

Oh, I’ve got the alcoholic blues, some blues."

— From "The Alcoholic Blues," 1919,

words by Edward Laska

The prohibition issue had been a constant companion of local politics since the creation of the Nebraska territorial legislature. In fact, one of the first acts of the territorial legislature was to outlaw the "manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages." But, the law was never enforced. In fact, there were saloons within blocks of the state capitol building, and this early prohibition law was repealed in 1858.

Prohibitionist sentiment seemed to grow with statehood. In 1890, the Prohibition Party nominated B. L. Paine, a prominent Lincoln merchant, as their candidate for governor and put an amendment on the ballot. The Populist, Republican and Prohibitionist political parties all supported the amendment, but the Democratic Party’s stand against prohibition was unchanged. The anti-prohibitionists forces ruled the day. The 1890 prohibition amendment and candidate Paine both went down to defeat.

In 1891, a limited prohibition amendment, known as the Slocomb Act, passed. The law permitted cities and towns, but not counties, to regulate saloons. It set a $500 minimum liquor license fee that could be assessed against those individuals wanting to operate saloons. The members of the Prohibitionist Party apparently concluded that if you can’t get rid of evil, tax it.

The drive to root out the evil of "demon rum" continued and would be a major political debate through 1920 and beyond.