In the early 1800s, the economic reality of what would become Nebraska was based on trade between the Europeans and Indians for furs and skins. Trading companies gambled fortunes in this high-risk enterprise, but the day-to-day business of the fur trade was done in Indian camps or at far-flung posts.

The fur trade was an international business with suppliers and customers half a world apart. But the actual trading took place at Indian camps or trading posts in the wilderness. Traders knew that the Indians needed tools to live well and produce the furs that made both the Europeans and Natives prosperous. All types of "trade goods" made their way into the fur trade from France, Spain, England, and the young United States.

Trade goods included glass beads from Italy, which replaced traditional dyed quills in beadwork. Belgian guns were made especially for the Indian trade. Beaver traps were shipped from the eastern United States. Other trade goods included whiskey, kettles, hoes, metal awls, nails, and metal arrowheads, pins, clay pipes and vermilion. The Indians were discriminating traders, as William Gordon recorded in 1831:

"Woollen goods of course fabric, such as blue and red strouds, Blankets etc. constitute the most costly items of trade — they are almost exclusively of English manufacture, and tho’ course are good — the Indians are good judges of the articles in which they deal, and have always given a very decided preference for those of English manufacture — knives, guns, powder, lead, and tobacco are also among the primary articles, some of which are American and some of English manufacture."

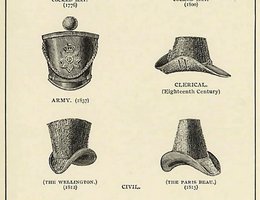

Europeans wanted beaver, raccoon, fox, mink, deer and even bear skins for the same reasons that Indians did — fur made warm clothing. The pelts were either sewn into coats or clothing or the hair was removed and then pressed, heated and chemically treated to make felt. The felt was then shaped into coats or hats. Beaver coats and hats were especially popular in Europe, and the European beavers had been hunted almost to extinction. Manuel Lisa’s trading company was one of the first to take advantage of this market.

Eventually the trade moved on to buffalo coats. The Plains Indians had countless buffalo robes. But before 1830, the robes were hardly worth what it cost to ship them to market. Then, the fur companies gradually organized better, and the steamboat came into general use on the Missouri River. Beginning in 1831, the cost of shipping buffalo robes dropped. The profits grew, and the fur trade with the Plains Indians blossomed through the 1850s.

The Native tribes traded for European manufactured goods — guns, knives, hatchets, beads, wool blankets, and other clothing were popular. Iron hatchets were a definite improvement over stone axes. Guns were better than bows and arrows. But the traders also brought whiskey, and alcohol was very addictive for the Natives. They had never been exposed to some of the dangerous diseases that the Europeans brought. The men who traded or trapped through the long western winters — when the pelts were at their fullest — developed a habit of taking Indian wives, even if they had another back east. The impact of European traders, and later trappers, was a mixed experience for the Native tribes.

As trade increased, the numbers of fur-bearing animals on the lower Platte and Missouri regions plummeted. Gradually, the source of pelts dried up, and fashions changed.

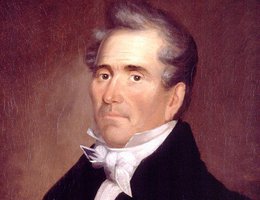

In 1806 the American explorers, Lewis and Clark, returned to St. Louis from their epic journey to the Pacific Northwest and confirmed rumors of teeming beaver steams near the headwaters of the Missouri River. Manuel Lisa, a St. Louis businessman, quickly organized a company for the purpose of taking advantage of this potential source of wealth. He left St. Louis in 1807 with two keelboats and 50+ men and ascended the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers to the mouth of the Bighorn where part of the company engaged in trade with the neighboring tribes. Weapons, blankets, costume jewelry, tobacco, and liquor were exchanged for just about any type of pelts the Indians could provide. The remaining members of the expedition were sent out to trap beaver, which was plentiful in the rivers and streams.

In 1814 Manuel Lisa built a trading post just north of Omaha. He is called Nebraska’s first white settler because he spent most of the winters in Nebraska. Later his wife, Mary, visited the post and was the first white woman in Nebraska. She spent the winters of 1819 and 1820 at Fort Lisa. Lisa’s first wife had died in St. Louis in 1817. He also had an Omaha Indian wife at Fort Lisa. It was not uncommon among the Indians for a man to have more than one wife, and early Indian traders very often married a wife in each tribe where they traded in order to make friends and help their business.

The success enjoyed by Lisa in this first expedition to the Upper Missouri led to more ambitious undertakings in future years. In 1809 he helped organize the St. Louis Fur Company and became one of its directors in 1809. In 1812 the company was reorganized and become known as the Missouri Fur Company of St. Louis. It underwent a series of reorganizations over the next ten years, but throughout the changes, Lisa remained the principal leader of the expeditions and the unifying figure in the company.

Fur traders, like Lisa, were a mixed blessing for the Indians. They brought trade goods, blankets, and other supplies, but they also brought whiskey which caused many problems. Lisa, however, saw himself as the Indian’s benefactor, not as an exploiter. In 1817, he wrote to a friend that he had distributed garden seeds to the Indians, including seeds of pumpkins, beans, turnips, and potatoes. He also indicated he had loaned them traps and arranged for "blacksmithing" to be done for them.

Manuel Lisa gained the reputation among trappers and Indians of being a great white man and leader. All the hardships and dangers of the frontier were nothing to him. He helped his men pull boats up the river, slept on the ground, and went periods without food. For twelve years he traveled over twenty-five thousand miles and spent three solid years on the Missouri River. He was one of the dominant figures in the upper Missouri fur trade during the last twelve years of his life. He died in St. Louis in 1820.