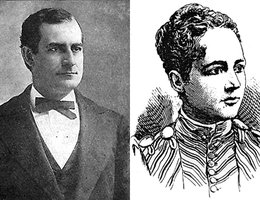

William Jennings Bryan fused Populist rhetoric and policies with a new Democratic coalition. In the process became one of Nebraska’s — and the nation’s — favorite sons. But, like many early Nebraskans, he was born somewhere else — in Illinois in 1860. His father was a lawyer and local politician. Both of his parents were intensely religious, and young William shared their fervor. At the age of 12, he joined the fight for prohibition of alcohol by signing a temperance pledge for school. After high school, attended law school in Chicago and worked in the office of Lyman Trumbull, Abraham Lincoln’s friend and a U.S. Senator. Shortly after Bryan began is own law practice, he married Mary Elizabeth Baird.

Bryan discovered Nebraska when he visited a law school friend in Lincoln after inspecting land in Iowa owned by his father-in-law. He saw Nebraska as a land of opportunity, and so Bryan moved to Lincoln and set up practice in partnership with his law school friend.

In 1890 — just three years after coming here — he decided to run for Congress as a Democrat. He was a long shot. No Democrat had ever been elected to Congress from Nebraska in its 20 years of statehood. But Bryan had realized that common people were in desperate financial times, and the Populist Party was probably at the height of its popularity. Bryan picked up some of the same ideas as the Populists. He won the election and then went on to win a second term in Congress in 1892.

In 1894, he decided against another term in Congress and instead made himself a candidate for the U.S. Senate. But the Republicans were back in control of the Nebraska State Legislature and they elected a railroad attorney for the Senate seat. Without a political seat, he became the editor of the Omaha World Hearld, at that time a Democratic paper. His writings kept his name and ideas before the public, and he also traveled the Chautauqua lecture circuit.

Through these campaigns, writings and public appearances, Bryan had become one of the nation’s best recognized advocates for the "free silver" policy. As the 1890s depression deepened, his ideas were catching on.

Free Silver was, by 1895, a political movement that was embraced by the Populists and the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. During the Civil War, President Lincoln had issued paper money, rather than gold coins, for the first time in the nation’s history. It was easier to print paper money than to mine or buy gold for coins, so there could be more money in circulation in the economy. That policy had helped pay for the war, but it had also stimulated inflation. So much paper money floating around tended to drive up prices. After Lincoln’s death, national Republican leaders had worked to make sure that every paper dollar issued was backed with gold. This is known as a tight money policy. When the depressions hit Nebraska and other agricultural states, it was more difficult for borrowers to pay back loans to the eastern banks. Reformers in the Farmers’ Alliance and other groups decided that backing the money with more plentiful silver rather than gold would make it easier for debtors to pay off their loans and remain on the farm. More money in circulation would make it easier for farmers to make some of that money and pay off their debts.

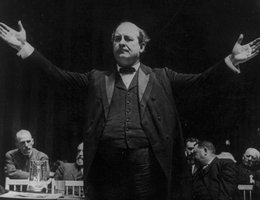

In the 1896 election, "free silver" was the central debate during the Democratic national convention. Bryan was selected as one of the main speakers. He gave a memorable speech, ending with all the righteous indignation he could muster:

The delegates were stunned. The cheers and applause went on for over 30 minutes. He was nominated for the Presidency on the fifth ballot. At the age of 36, he was the youngest candidate nominated for the presidency up to that time.

Bryan was running against Republican William McKinley who advocated conservative policies and ran a "front porch" campaign — McKinley stayed at home and had groups of supporters come to him. Bryan, on the other hand, traveled over 18,000 miles and made over 600 speeches. Some days he would give 10 or 20 speeches. But it was not enough against the better financed Republicans. McKinley got 51 percent of the vote to Bryan’s 47 percent.

Over the next four years, the political situation changed. The economy came out of depression and the country entered the Spanish-American War. Bryan raised a regiment of mostly Nebraska volunteers for the war, but President McKinley didn’t want Bryan to get any glory and the regiment sat out the war in Florida. In 1900, Bryan was still the dominant figure in the Democratic party, and he got the party’s presidential nomination. But silver was no longer the rallying point it had been. So, Bryan took up the anti-imperialism cause — he argued that it would violate the essence of American democracy if the U.S. created an empire by taking over the Philippines from Spain.

Some Spanish-American War Medal of Honor recipients are in the Nebraska Hall of Fame.

Bryan was defeated by Taft again. This time he came home and began publishing the newspaper The Commoner from Lincoln. The 16-page weekly paper was mailed to up to 140,000 progressive supporters. That exposure, along with an aggressive schedule of speaking engagements, kept Bryan as a major figure in the Democratic party.

However, in 1904, the party endorsed the gold standard, nominated a strong gold supporter and lost the election by a landslide to Theodore Roosevelt, who had become President after McKinley’s assassination in 1901. Roosevelt had adopted some of Bryan’s progressive policies and was a charismatic candidate.

Bryan was nominated again in 1908 and ran against Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor, William H. Taft. That election was the first to make use of recorded campaign speeches issued by the two opposing candidates. Some phonograph dealers put on "phonograph debates" with mannequins propped up in the stores as stand-ins for Bryan and William H. Taft. These were popular with the public and proved to be great fun. Despite his oratorical skills, Bryan lost the election to Taft.

In 1912, Bryan helped Woodrow Wilson win the presidency and Wilson named Bryan Secretary of State. He served for two years, negotiating peace treaties with 29 nations. He also helped Wilson push through a series of domestic reforms known as the "New Freedom" measures. But when Wilson began to push the country towards involvement in the First World War, Bryan resigned.

He turned his attention to other issues, saying that the three great reforms of the 1920s would be peace, prohibition and women’s suffrage. His support was significant in passing the latter two causes. At the end of his life, he was more and more concerned with religious issues and he became even more famous for his prosecution of the Scopes monkey trial. He argued against the teaching of evolution. Five days after the trial ended, Bryan died in his sleep in Tennessee.

In many ways, Bryan was ahead of his times. Despite his fundamentalist religious views, he was a progressive politician. The ideas he promoted unsuccessfully in 1896, were adopted by Teddy Roosevelt’s platform in 1904. He supported the adoption of the Federal Reserve Act, the Federal Trade Commission, control of trusts and monopolistic companies, government control of currency and banking, voting reform and regulation of campaign contributions. Before Bryan, the Democratic Party was a conservative party of Civil War losers. After Bryan, the party was a progressive alliance of small businesses, farmers, blacks and blue-collar workers. It was this alliance that later elected Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

William Jennings Bryan is in the Nebraska Hall of Fame.