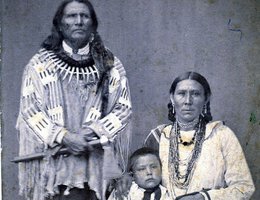

The Ponca were very unhappy with the land and living conditions on the Quapaw Reservation. Much of the land was not suitable for cultivation; sanitation conditions were deplorable. Government agents refused to provide adequate farming equipment, and many of the people died from malaria. Since leaving Nebraska, nearly one-third of the tribe had died. In January 1879, Standing Bear’s son, Bear Shield, died. The distraught chief decided to return to his tribal lands in Nebraska to bury his son. It was another terrible trip, but on March 4, 1879, Standing Bear and his followers arrived at the Omaha Reservation.

Standing Bear and his followers left the Indian Territory without permission from the national government, and they were to be arrested and returned to Indian Territory. The arrest order trickled down the line of communications from General Sherman in Washington, to General Sheridan in Chicago, to General Crook in Omaha.

Under Crook’s orders, Lieutenant Carpenter and four of his men arrested Standing Bear and his followers and escorted them to Fort Omaha, where they were to be held prior to returning to Indian Territory.

Standing Bear and other members of the tribe were placed in detainment at Fort Omaha on March 27, 1879. Post Commander, Colonel John H. King, reported the serious illness among the Ponca and the weak condition of their horses made it impossible for the Indians to return to Indian Territory at this time.

The delay worked in favor of the Ponca as the Standing Bear situation came to the attention of Thomas Henry Tibbles, the assistant editor of the Omaha Daily Herald. He was an ardent crusader who sympathized with the Indians.

There is some question concerning how Tibbles found out about the case. In 1880,Tibbles said he was informed about the case by the city editor of his newspaper, the Omaha Daily Herald.

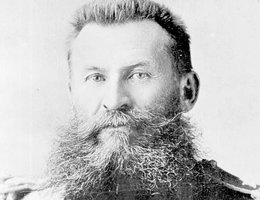

But, years later — after Crook’s death — Tibbles indicated that the true account of how he became involved in the Standing Bear affair was through General Crook’s intervention. He reported a conversation with Crook.

Crook is supposed to have said,

"I’ve been forced many times by orders from Washington to do most inhuman things in dealing with the Indians, but now I’m ordered to do a more cruel thing than ever before."

If we look back at the history of the American west, the popular view is that the Army was brutal and wanted to exterminate Indians. This is a view made popular by a progression of novels, movies and television programs.

There was brutality, but not every Army officer in the West was bloodthirsty. Many were sympathetic with the plight of Indians and opposed policies of the government that seemed intent on moving all Indians to Indian Territory.

As late as 1871, Gen. Crook had written to President Grant and officially expressed his opposition to aspects of government Indian policy. But his feelings never became public because Crook decided it would be inappropriate for him to take a public stand. After taking command of the Department of the Platte, he came to the conclusion that his official reports were not very productive.

However, by 1879, he became much more vocal in his criticism of federal Indian policies. General Crook interviewed Standing Bear and several of his tribesmen on March 31, 1879, at Fort Omaha. Journalist Thomas Tibbles was invited by Crook to attend the meeting. General Crook asked Standing Bear why he had left the Indian Territory, and Standing Bear replied,

"At last I had only one son left; then he sickened. When he was dying, he asked me to promise him one thing. He begged me to take him, when he was dead, back to our old burying ground by the Swift running Waters, the Niobrara. I promised. When he died, I, and those with me, put his body into a box and then in a wagon, and we started North."

After Standing Bear had spoken, Crook expressed his sympathy with the Ponca, but stated that he had a direct order and would have to obey it. "It is . . . a very disagreeable duty."

The plight of the Ponca convinced General Crook that he had to become more aggressive in expressing his views. Crook’s position brought him into open conflict with government policies, but it also brought him into a closer alliance with the group of civilian reformers he had earlier mistrusted. Thomas Tibbles quotes Crook as saying he would resign his commission if he thought it would help keep the government from forcing the Ponca to return to Indian Territory. He also was quoted as saying he would appeal directly to Washington, except that the government typically issued orders that were the exact opposite of what he recommended.