The large Siouan tribal language group was made up of many smaller tribes such as the Ponca, Omaha, Osage, Kansa, and Quaqaw tribes. These five tribes once lived in an area east of the Mississippi River, but just prior to Columbus’ arrival, they had begun moving westward. The Ponca and Omaha split from the other tribes sometime prior to 1500. According to tradition, the Omaha and Ponca followed the Des Moines River to its headwaters and then moved northeast.

Eventually they crossed the Missouri River and drove out the Arikara Tribe that lived on the west bank of the Missouri River in an area that would later be included in the state of Nebraska. Sometime after the encounter with the Arikara, the Ponca and Omaha separated. The separation date has been placed as early as 1390 and as late as 1750. Certainly by 1789 the Ponca were living on lands where the Niobrara flows into the Missouri. The Ponca Tribe was never very large. Between 1800 and 1900, they probably never numbered more than 800.

They appear on P. C. LeSeur's map of 1701 and were "discovered" again by the trader Juan Baptiste Munier in 1789. By that time there were living near the mouth of the Niobrara River. About that time they suffered heavily from a smallpox epidemic. Lewis and Clark estimated that they numbered only 200 people in 1804. By 1874, they were back up to 733 individuals, all living near the Niobrara.

Standing Bear was known to the Ponca Ttribe as Ma-chu-nah-zah. He was born on the Ponca reservation around 1834, although some sources say he was born in 1829. Because he showed unusual abilities, he became a chief at an early age.

The complicated relationship between the Native American tribes and the U. S. government is outlined in this quote:

“Indian Nations had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural right, as the undisputed possessors of the soil . . . The very term ‘nation’, so generally applied to them, means ‘a people distinct from others’." — John Marshall, 1832 Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515,561

The Ponca Tribe signed several treaties with the federal government from 1817 to 1865. Like numerous other tribes in Nebraska, they were forced to witness the shrinking of their homelands until most were moved to the Indian Territory in the present day state of Oklahoma.

The United States government signed four treaties with the Ponca before ending the treaty-making procedure to formalize relations between them and the Indians. Treaties were signed with the Ponca in 1817, 1825, 1858, and 1865. The third and fourth treaties are the most significant with reference to the 1879 Standing Bear v. Crook court case.

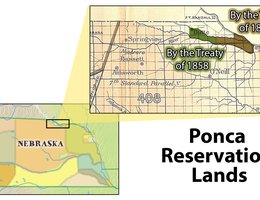

In 1858, the Ponca ceded a large section of land to the U.S. Government, but they did reserve a much smaller area for the tribe to occupy. They agreed to move to the reserved area within one year after ratification of the treaty. The new area would become their permanent home. In return for making the land cession, they were to receive the following from the U.S. Government:

1. Annuities — that is, cash payments — for 30 years

2. Educational institutions for ten years

3. A mill to grind grain and one to saw timber

4. An interpreter, a miller, a mill engineer, and a farmer

As the Commissioner for Indian Affairs explained in his 1858 Report, the objective was to "colonize and domesticate" the Ponca.

The Ponca planned to give up hunting for an agricultural economy. However, they faced a variety of problems that included: failure of the government to live up to its promises, drought, locust, and conflicts with the Sioux. Yet, the Ponca kept their promises and never stole from nor attacked the white man.

Another treaty was concluded in 1865 with the Ponca agreeing to relocate their reservation to the east and south of its earlier location. The tribe gave up most of its 1858 reservation in exchange for lands surrounding them south of the Niobarara River and Ponca Creek. They were also given islands in the Niobrara lying "in front" of the new reservation lands. This treaty provided for a reservation of 96,000 acres in the present day Nebraska counties of Knox and Boyd. The treaty stated that the reasons for this move were to return to the Ponca their old burial grounds and to return their traditional agricultural lands. A third reason was to move the Ponca away from the Sioux who were attacking from the West.

Unfortunately for the Ponca, in 1868 the U.S. Government signed a treaty with the various bands of the Sioux Nation. This treaty, often called the Fort Laramie Treaty, created a large Sioux reservation that included most of South Dakota west of the Missouri River. Unfortunately, the southern boundary of the South Dakota area also included parts of the land reserved for the Ponca in the 1865 treaty. Consequently, about 96,000 acres of the tribe’s land (the bulk of their land) was given to the Sioux.

How could this happen? Most likely because the Fort Laramie Treaty commissioners (Generals Sherman, Harney, Terry, etc.) had forgotten about the provisions of the 1865 treaty with the Ponca. Thus, two different tribes were granted the same land.

That set the stage for the Ponca Tribe’s "Trail of Tears."