While Crook watched over the Ponca at Fort Omaha, Tibbles worked feverishly to tell Standing Bear’s story and enlist support for the Ponca cause. He telegraphed the story of Crook’s interview with Standing Bear to eastern newspapers and wrote a very passionate editorial for the Omaha Herald on April 1, 1879. Tibbles enlisted the support of the ministers of the leading churches in Omaha and sent a telegram to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, pleading with him to reverse his removal order.

Thomas Tibbles wrote,

"Therefore in spite of my double night tasks for the Herald, I stole my forenoons from sleep to spend them in a law library. I had to devise a case and a method which could release these abused Poncas — and then could recast our nation’s whole Indian Policy."

Tibbles then roughed out a court case, based on the newly approved Fourteenth Amendment, and took it to his friend John L. Webster, a young lawyer in Omaha, and to A. J. Poppleton, the chief attorney of the Union Pacific Railroad. Both men agreed to represent Standing Bear and the Ponca without a fee.

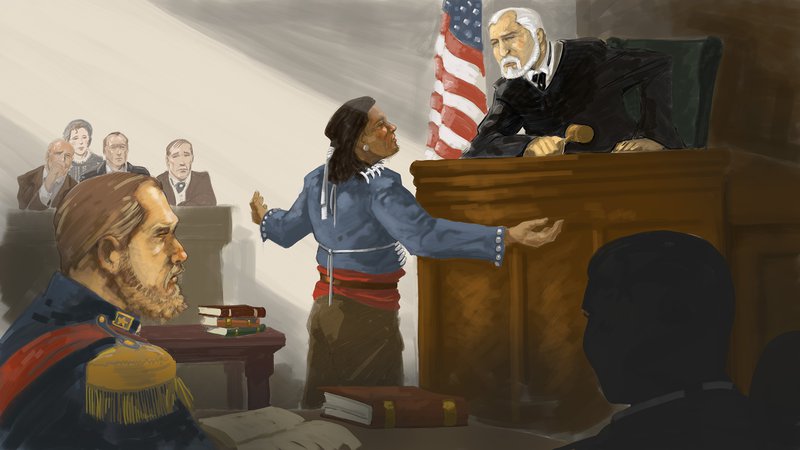

The two attorneys then petitioned Judge Elmer S. Dundy of the United States District Court for a writ of habeas corpus to compel General Crook to justify his arrest of the Ponca. Dundy, known to be sympathetic to the downtrodden, issued the writ and ordered the opposing parties to appear before him.

The trial opened in Omaha on April 30, 1879, and lasted for two days. G. M. Lambertson represented the U.S. Government and their argument was simply that the Indian was neither a person nor a citizen within the meaning of the law, and therefore could not bring suit of any kind against the government. Lambertson further contended that the Ponca adhered to their traditional ways, were dependent on the government, and as Indians, were not entitled to the rights and privileges of citizens.

The attorneys for the Indians stressed that the Ponca had renounced tribal authority, were engaged in farming, had made great advances in assimilation, and were entitled under the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to be treated like other people. The lawyers also argued that the U.S. Government had no right to take the Ponca’s land or move them to Indian Territory.

After the attorneys presented their arguments, Judge Dundy allowed Standing Bear to address the court. Standing Bear did not speak English, but he was able to make an eloquent plea to the court through his interpreter, Susette ("Bright Eyes") La Flesche.

Standing Bear rose, extending his hand toward the judge’s bench:

"That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both."