In the late 1700s, Spanish officials in St. Louis decided to expand their trade up the Missouri. To do that they needed to protect the river from incursions from competitors and they needed to build a series of fortified trading posts. In the 1790s Spain began patrolling the Missouri and Mississippi rivers with gunboats. The boats were called galiots (pronounced gah-le-OATs) were about fifty feet long and armed with cannons. A galiot could usually be rowed or sailed by their crew of 26, but there were times it had to be pulled along from the bank at the end of a long rope.

What the gunboats were protecting was an exclusive fur trading monopoly that was granted to a group of St. Louis merchants called the Company of Explorers of the Upper Missouri in 1794. Their task was to explore the Missouri River and build a chain of forts along it. The merchants hired the able James Mackay as their field manager. He was actually a Scotsman, but the Spanish decided to call him "Diego McKay."

Mackay brought his trading expedition up the Missouri to a site a mile above the mouth of the Platte. There on October 14, 1795, they began building the "Post of the Otoes" in what is now Nebraska or Iowa. This trading post served the Oto Indians, who lived a few miles upstream. It was relocated eight miles south of the Platte in 1797, and then abandoned later that year.

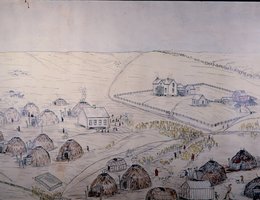

That same year, in November of 1795, Mackay laid out Fort Carlos IV (Fort Charles) on a tiny rise of ground in the Missouri floodplain a mile from the Omaha Indian village near present-day Homer, Nebraska. Fort Charles was named in honor of Charles IV of Spain. Fort Charles was an impressive stockade with corner bastions, a storehouse, living quarters, and a trade room for the Omaha.

Mackay’s journal provided a clear description of the fort’s surroundings:

"On the 29th [of November, 1795], the Prince (Blackbird) came to visit the fort which was being built in a plain located between the very village of the Mahas and the Missouri River, on the shore of a small river which flows into the latter, and is fairly navigable. This plain is very extensive, the land excellent, and never inundated by the waters. The location of the fort seems to have been prepared by nature. It is in a commanding district, which rises for a circumference of about one thousand feet. It looks on the shore of this river, as if to command the rest of the area. I have established my settlement and my fort there, although at a distance from the woods; however, the horses of the Prince are at my service."

The Native American village was called Tonwantonga (Large Village) by the Omaha and was ruled by the great chief Blackbird. An estimated 1,100 people lived in this earth lodge town about 1795. It played an important role in Indian and exploratory history. In 1800, however, disaster struck the village as smallpox killed an estimated 400 people, including Blackbird.

Fort Charles and the Post of the Otos were the first Spanish fur trading posts in Nebraska that we have documented evidence of. They may not have the first EuroAmerican post in the area, however, for Mackay’s journal left little doubt that he believed an English fort had been built the previous year somewhere near the Omaha village in either Nebraska or Iowa. In January 1796, he wrote:

"The English of the river of San Pedro [the St. Peter’s or Minnesota River] had concluded among this tribe last autumn [apparently in 1794] the construction of a fort for them on the shore of the Missouri, which they were resolved to maintain against all resistance."

Competition from the British and mismanagement forced the Missouri Company to liquidate in 1797, leaving over $100,000 in debts. The Spanish plan to build barriers against the British and French was ineffective and the Spanish Government returned to issuing tribal trade monopolies to individual traders.

The Spanish presence on the upper Missouri River would, in the course of time, become only an extended footnote in history. One of the principal results would be their legacy of maps that Lewis and Clark would find so faithful in their first year of travel.

During the latter part of the 17th century, Native Americans in what would become Nebraska were starting to trade for European goods, such as glass beads and metal items. In the early years, these items may have traveled through tribes in the east who were in contact with the Europeans. Later, goods came directly from European traders visiting the area.

The Plains Indians acquired guns in the 17th century from French and British Traders. However, these weapons did not replace the bow and arrow. While both guns and bows and arrows were used for hunting and warfare, the gun was preferred in battle because of its greater range, accuracy, and penetration. Guns also contributed to the migration of the various Indian tribes as the tribes who received access to guns first, forced neighboring tribes to move further west.

The first guns used by Nebraska Indians were lightweight, smoothbore, French flintlock muskets. Some were used against Villasur in 1720. By the end of the 1700s the British Norwest gun, with its serpent plate trademark, became the firearm of choice.

Unfortunately, the first white men to meet Plains Indians probably also carried alcohol as a trade item. Whiskey and other forms of alcohol soon became known as "firewater" and became a problem for tribes across the plains. Its use in the fur trade was widespread. Even though some governments banned the sale of alcohol to tribes, it was still carried by many government expeditions. Pure alcohol was brought into Indian country, but it was usually diluted with water before it was sold or traded to the Indians. Bottled spirits, like wine and patent medicines, came later. Most traders protested the use of alcohol, but claimed they were forced to use it because their competitors did.