The first rumblings of the 1980s’ farm crisis came in the 1970s. In the early years of the decade, prices for farm products were relatively high. In 1973, farmers across the nation had a total net income of $33 billion. By 1977, record crops had pushed prices down, and the cost of fuel, seed, pesticides and other farm costs had risen — net farm income dropped to $20 billion. In addition, the value of farm land — the "equity" or value that farmers use to secure loans to operate each year — had dropped. Banks were no longer willing to loan to smaller farmers. Many were in danger of losing their farms.

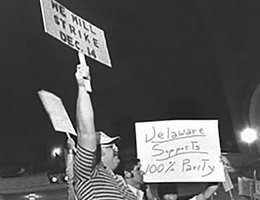

Farmers on the Plains, particularly, were so desperate that they decided to strike if the government wouldn’t guarantee high enough prices for their products to cover their costs and a reasonable profit. The movement began in Springfield, Colorado, where a group of farmers got together and developed the strike idea. They called on farmers across the country to stop buying or selling anything on December 14, 1977, unless their demands were met.

Strike plans proceeded. The core demand of the group was for "parity." Parity is a statistical model that looks at what it costs farmers to buy the materials they need to farm and the prices they get for their crops. The designers of the model decided that in the period between 1910-14, an average farmer’s income and expenses were in rough balance. He or she made enough money in selling farm commodities to support a reasonable standard of living. The economists then factored in inflation rates and current prices for commodities in a given year to come up with parity levels. In 1977, the "parity level" was estimated at roughly 66 percent. In other words, some economists said that the buying power of farm commodities had dropped by a third. These economists and activists estimated that full parity prices for farmers would have resulted in a 20 percent increase in the cost of food to the consumer, despite the fact that most of the cost of food goes to processors, transporters and distributors, not farmers. Other economists disputed the whole scientific basis of parity.

On December 10, farmers across the nation rallied at their state capitals to support the strike. Nebraska farmers joined in and drove their tractors from the Capitol building to the Devaney Sports Center for a rally. Despite freezing temperatures, even Gov. J. J. Exon rode on an open tractor to the rally. Officials counted just over 5,000 vehicles entering the Sports Center and estimated the crowd at 6,000.

Exon told the crowd of farmers,

"They said it would be a cold day in hell when farmers would get together. I can’t tell you how warm it is to have you here in Lincoln. I only wish we had had such a rally two or three years ago. ‘Strike’ is not a usual word with farm people; these are not usual times. We need to get the message across to everyone that there is a problem. The farmer gets 31 cents of the food dollar while the labor processor gets 33 cents and the transportation and marketing segment get 36 cents. Unless we can get more than 31 cents for the farmer, we won’t have our food plant sustained."

Burt Evans, a University of Nebraska economist, urged the farmers to hang together or hang separately. "Getting the government out of agriculture is nonsense," he said. "We need good, sound programs all the time. A good farm program has to be there all the time."

One farmer said he planned to put a sign on his tractor indicating it had a usable life of about 10 years, but that it would take him about 15 years to pay for it because of low prices for agricultural products.

Signs were everywhere, and many got the attention of reporters and observers. They were known as "Deere John letters", creating a pun with the name of the tractor manufacturer.

The rallies in the Plains states were the largest, but a majority of agricultural states did participate. Even President Carter’s sister participated in a tractorcade in Georgia. Gloria Carter Spann rode in a lawn chair on top of a tractor owned by her husband. She said, "Farmers are united for the first time, I’ve never been so proud of farmers."

The rallies created a lot of attention, but the strike did not go as planned. The Omaha World-Herald did a poll in Nebraska to see what Nebraskans thought about the proposed national farm strike. A majority of Nebraskans interviewed said they approved of a farm strike. However, a similar majority of farmers interviewed said they did not plan to participate in the strike.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics showed that U.S. farm production continued to increase from 1977 to 1978. In short, the strike had absolutely no effect on food and fiber production. But the movement did show the hard times that farmers were facing.

This was not the first time that a strike had been proposed. During the 1930s, farmers in Nebraska and Iowa actually blocked roads leading to agricultural markets to try and force other farmers to keep their products off the market. That strike was short-lived as well. Getting any large and diverse group, like all farmers, is extremely difficult. But the movement did dramatize the hard times that farmers were facing.