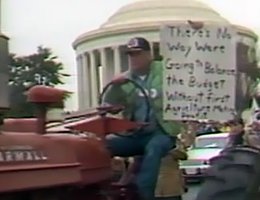

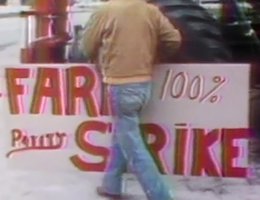

The year after the first strike, the American Agriculture Movement decided to take their demands and their tractors to Washington DC. They were demanding a revision of the 1977 Farm Bill. They argued that the bill encouraged large scale production, but did not guarantee of high enough prices to keep small farms in business. The AAM emphasized rallies and protests against the political system.

A protest rally in the nation’s capital was planned for January, 1978, which would bring a nationwide focus to the organization and the strike. Nearly 3,000 farmers drove their tractors into town on the interstate highways. Many had traveled across the country to get to the rally. Along the way, many protesters stopped in local congressional offices in order to explain their position.

As one of the participants remarked enthusiastically, "They [congressional staff] poured out of every corner to meet with us — when I saw all that, I knew we were damned important."

The farmers did achieve a minor legislative triumph — the Farmers Home Administration, which lends money to farmers who can’t get financing anywhere else, imposed a moratorium on all foreclosures. In other words, the FHA would temporarily stop taking the land and equipment pledged in security for loans that farmers could not repay. But, the moratorium was short-lived. It was a symbolic act that later gave way to economic realities.

In 1979, the AAM was back in Washington again, even more angry as the farm crisis deepened and more farmers lost their land. There were nearly 900 vehicles for the second tractorcade, but only half the number of farmers. This time, they refused to park peacefully at a local stadium. Instead, they tied up traffic and damaged some federal facilities. Finally, the police confined them to the Mall area.

This time Washington did not open its doors. Most legislatures would not meet with AAM representatives and, in retaliation, many farmers became belligerent and threatening, which further isolated them from their congressional representatives as well as the general public.

The protesters stayed, camped out on the Washington Mall. During that time a blizzard hit the city with 20-inches of snow. Farmers used their tractors to help dig out the city. Some tractors transported doctors and nurses to hospitals. AAM women even cooked and cleaned in hospitals when other staff couldn’t make it in. By midwinter, most of the protestors had left DC.

Kenneth Hilton, a Nebraska farmer from Cambridge, was one of the protestors who was arrested by DC police for becoming too belligerent. Police tried to stop a line of tractors from forming in an unauthorized area, and Hilton’s tractor rammed two police scooters. Police pulled Hilton from his tractor and wrestled him to the ground. Hilton was charged with two felony counts of assaulting police officers and eventually was fined $1,000.

In 1987 Hilton filed for Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code which was created to allow businesses and farms to reorganize and resume business. Hilton said he was "going through some very stressful times" and was not sure he would be able to resume farming if crop prices remained low.

The American Agriculture Movement played a short but central role in the politics of U.S. agriculture. They used modern media technology to reach both farmers and the general public to an unprecedented degree. Unfortunately the media technology that the AAM used so effectively, later became a negative factor. Media coverage was critical of the more violent protests and public opinion changed. But the organization still exists and still lobbies on Capitol Hill, pushing the opinions of its farmer-members.