Verdigre is a small, close-knit Nebraska community of around 600 people near to the South Dakota border. In September, 1984, the Bank of Verdigre closed and its assets and outstanding loans were seized by Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or FDIC. The FDIC, of course, was set up in the 30s to protect the depositors in a bank, and so when a bank has bad loans, the FDIC tries to recoup as much as possible from the collateral put up on the loans.

What happened in Verdigre was an example of how hard the farm crisis was on a community, and how others rallied to support those in trouble.

In Verdigre, the FDIC was aggressive in trying to protect depositors. They sometimes seized up to 100 percent of a farm borrowers’ assets and of the proceeds from livestock and grain sales. Farmers found that they could not collect money from the sale of their farm crops and livestock without giving much of the revenue to the FDIC. Many times farmers did not have enough cash in reserve to feed their families or livestock. That had a ripple effect in the community. When a farmer can no longer buy things in town, the whole community is affected. Verdigre leaders urged the FDIC to be more humane and work with farmers to repay their loans, but FDIC officials said they were required by law to protect depositors by seizing the assets of delinquent borrowers.

FDIC spokespersons asked,

"Is it inhumane to enforce the law?"

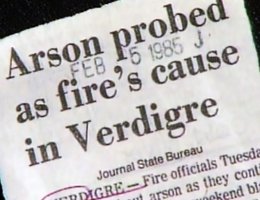

Others may not have agreed. In 1985, someone burned the FDIC office in Verdigre.

Losing the main financial institution in a community creates stresses. Many farm families, unable to pay off their bank loans, experienced emotional problems. For example, when the Bank of Verdigre closed, the FDIC assumed the $150,000 in loans from Jim and Barb Sokol. The FDIC ordered the creameries and livestock dealers that did business with the Sokols to endorse checks to both to the FDIC and the family. Then, the FDIC kept 100% of that money because of the Sokol’s debts and the farm’s inability to show a profit.

Jim and Barb said they felt confused and a little ashamed about how they got into financial trouble. They blamed lenders for extending them too much credit and the government for setting high interest rates and low commodity prices.

Jim Sokol said the hardest stress was on the family.

"It gets to the point where we start arguing rather than just discussing business. When the FDIC took over and shut the door on everybody and said, ‘You won’t get your milk check,’ it’s just put pressure on and that’s all there is to it."

Their daughter Cookie Sokol was 10 when her family was in trouble. She said she tried not to listen when her parents argued about how to save the family farm. She said her parents argued "about the money and stuff that they don’t have."

But, Verdigre found they were not alone in their suffering. Other communities and organizations in northeast Nebraska came in to help. Food for families flowed into Verdigre from all over the nation. For example, a retired nurseryman from Kansas City, Missouri drove his pickup truck, loaded with 35 boxes of groceries that cost him $600, to Verdigre to help area farm families.

A "Food Bank" for people in need is nothing new. But in Verdigre, they also set up a "Feed Bank" to provide livestock feed to cattle and other animals. The idea came from Father Ronald Battiato and some of the community leaders he was meeting with. A plea went out to farmers and organizations around the state and the region, and people responded by donating grain for feed. The National Farmers Organization alone sent 3,000 bushels of grain to Verdigre. Then, the grain was distributed to those under stress.

Fr. Battiato said he was sure that the grain was going to those who really needed it. "When we give grain to someone, we reserve the right to verify need." He said that wasn’t a problem because, "Everybody knows everybody else, anyway."

Through the help of others and a ties that hold a small community together, Verdigre was able to weather the crisis. Some families lost their farms. Some left. But the community was still able to celebrate the centennial of their founding in 1987.

Fr. Battiato told the community then,

"A centennial [celebration] is really a time for us to remember what people have done in years gone by, recent history and the way people rallied to come and help Verdigre in a crisis that we had. But going way back, [we remember] the crises they had in earlier days are no less significant. And I think the response really represents what America is all about."