Underlying the Farm Crisis of the 1980s, there was a raging debate over what were the best kind of farms. Farms were getting larger, and many farms were organizing themselves into corporations. Activists believed that family-owned farms were better than corporate farms. In Nebraska, the debate was played out in a battle over the constitution of the state.

We should define some terms. A family farm can be set up as long as one family or and individual has enough money, or can borrow enough, to rent or buy the land, equipment, seed, fertilizer, pesticides, livestock, and other inputs that are needed to grow food or fiber products. All of the assets are owned by the individual or family, as are all the debts as well. Usually, all of the decisions are made by the person who’s going to be doing most of the work.

A corporation can also be set up by an individual or family. Or, it can be a huge organization. What defines a corporate farm is that it is organized as a legal entity with certain rules. There is a management team, a board of directors, and a list of owners, each of whom has put up some of the money that the corporation uses to operate with. The list of owners can be short or run into the millions. Corporations have different tax rules than individuals. If a corporation goes out of business, the owners will lose the money they invested to own the corporation’s stock, but they won’t lose any of their own personal property. On the other hand in a family farm, lenders can go after everything the individual owns to satisfy the debt. Corporations can also be passed down to the new owners if a manager or owner dies.

Supporters of corporations say they can be more competitive, have higher productivity and can produce food cheaper and more efficiently than small family farms. Corporate owners contend they can bring stability to agriculture and security to farmers. Through efficient large-scale production, they will be able to produce large quantities of agricultural products that will translate into cheaper food prices for the consumer. Most offer a set wage, insurance benefits, and retirement options to workers. Also, workers can clock in at 8 A.M. and leave at 5 P.M. Many corporations will purchase farmland because it has been a good long-term investment. It also offers tax benefits. One insurance representative explained,

"We can use the speeded-up depreciation on everything — tractors, equipment, buildings and other capital improvements."

Critics counter that corporate farms throw large numbers of people off the land. As family farmers leave, they leave behind wasted towns, deserted communities, depleted resources, empty institutions, and people without hope and without a future. Owners of corporate farms may live hundreds of miles away and know little about the land itself or the community around it. All they care about, critics say, are profits. Some corporate farms have been accused of destroying the land, for example, by plowing fragile land in the Sandhills to put in center pivot irrigation machines and then abandoning the land to the sand when crop prices drop.

Corporate farms are generally larger, so they can buy directly from the fertilizer factories and other suppliers that are located in urban manufacturing centers. They can ship huge quantities of goods profitably to major markets far away, bypassing local markets. Declining population and the transfer of profit centers create additional community changes. For example, the local hardware and grocery stores may merge, churches may merge, and schools may consolidate. Services once provided in small towns are no longer available, and so more people leave the area.

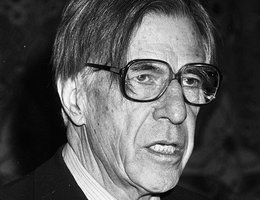

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith has argued,

"We are becoming the servants in thought, as in action, of the machine we have created to serve us. Corporations no longer serve us. We serve them."

For critics of the corporations, the family farm is more than a business — it is a way of life. To non-family corporations, farming is just a business.

The debate over corporate farming was a very emotional issue in the late 1970s and early ’80s. So, a group of activists proposed a constitutional amendment that would outlaw most forms of corporate farming in Nebraska. To get the amendment on the ballot, they had to circulate an initiative petition across the state and convince voters to sign it. They did, and the ballot measure became known as Initiative 300.

Here are the key provisions of Initiative 300:

The amendment also contains a long series of statements spelling out what was and was not restricted by Initiative 300.

If a corporation tried to get around the amendment, the Secretary of State would be able to detect violations because corporations have to file all their legal papers with that office. Corporations would then be forced to sell (within two years) any land held in violation of the constitutional amendment.

In the election of 1982, the corporate farm debate was heated, in part because local farmers were in a bidding war for ag land with large corporations like the Omaha National Bank, Prudential Insurance and others. Farmers have traditionally been the largest group of land buyers, and some were finding themselves unable to compete with the corporations.

Throughout the summer and fall, speakers from both sides crisscrossed the state. Newspapers editorialized on one side or the other. In the end, Initiative 300 passed and became part of the Nebraska Constitution. It was passed 290,377 to 234,555.