Unfortunately, a time machine does not exist that would enable you to take a journey back 12 million years ago. But, the Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park may be the next best thing.

The park is located between Royal and Orchard in Antelope County in northeast Nebraska. Inside, the animals are still locked in their death-poses and are amazingly well preserved skeletons. Michael Voorhies and his colleagues made the decision to excavate the site and leave the animals in their positions, rather than removing the skeletons to the museum. Visitors can visit this time capsule and view what Nebraska wildlife was like long before modern human beings ventured onto the Great Plains.

Ashfall is unique in that animal skeletons are still joined together in the proper order, not bones scattered over a wide terrain over a long period of time. The silent, ominous cloud of ash that rolled across Nebraska and eventually buried the animals has preserved them and offers scientists and visitors a unique glimpse into their lives.

After the discoveries at Ashfall, there was a great need to protect the fossils and allow the public to see them. This segment shows the process of building the Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historic Park.

From the 1992 NET Television program Mysteries in the Dust

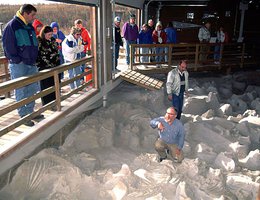

Today, visitors can step into the "Rhino Barn" built directly over the working excavation. They can meet Morris, McGrew, Dr. Marie, and Delia — all rhinos and horses who are ten million years old. Morris was a male rhino with large tusks and big feet. McGrew was a female rhino with small tusks and an unborn calf. Dr. Marie was a small three-toed horse. Delia was a young horse who still had its baby teeth. You can almost sense the agony the animals must have felt in the last moments of their lives.

Excavation of the Ashfall site continues and hopes are high that a skeleton of one of the large extinct predators, like a saber-toothed cat or a beardog, will be found. Bite marks on bones already collected and fossilized droppings full of chewed bone give proof that big meat-eaters were close at hand. Perhaps some day a park paleontologist will brush away the ash from a gleaming saber of a great rhino-killing cat, exposing it to the sunlight for the first time in ten million years.

The ash bed fossils provide us with much new information about the anatomy and behavior of many members of the ancient grassland animal community.