The Central Plains Village Tradition period (from 900 -1450 CE) saw a rapid increase in population on the plains and, in one sense, was the culmination of the changes that began during the Plains Woodland period. Archaeologists estimate that there were more people in the region during the period than at any other time before or since. In other words, there were more people living on the plains than there are even now. About 5,000 archaeological sites have been discovered in Nebraska and fewer than 50 can be attributed to historic tribes, that is the tribes in Nebraska after 1750. Most of the sites were inhabited between 1000 and 1400 CE In addition, the Central Plains Tradition cultures perfected hunting with bows and arrows and farming with bone and stone tools. These people lived in thousands of small permanent farmstead settlements throughout the eastern two-thirds of Nebraska.

But even though they carried on traditions that had begun with the Plains Woodland people, archaeologists are unsure whether the new culture migrated to the plains from the south or developed from the older one. The Central Plains Tradition culture is so distinctive that they cannot be associated with any earlier cultural group, whether that group was from other parts of North America or the local Plains Woodland groups.

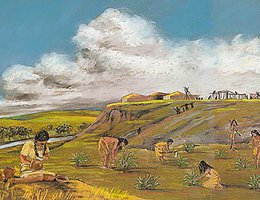

What set Central Plains Tradition people apart is that they were farmers who lived in centralized villages. They began to raise significant quantities of corn, beans, squash and other crops. An improved strain of corn produced food surpluses. Garden hoes were made from bison shoulder blades. The village farmers also developed better ways to store their produce. Archaeological exploration of Central Plains Tradition earth lodges have found bell-shaped underground pits that are thought to have stored corn.

Native American people still hunted and gathered wild plants, but their gardens became a much more important source of food. While they did hunt the bison, archaeologists disagree over the importance of the bison to the villagers. The plains during this time experienced frequent cool droughts, and the bison population seems to have been smaller than during the later Historic time period. Consequently, large bison herds were not always available. So, it is possible that the more intense use of small garden plots was a response to the thinning of wild game and wild plants.

As the gardens and first farms grew, so did the size of the villages. The successful cultivation of domesticated crops coincided with an increase in prehistoric Indian populations.

To house this increase in the number of people, the earth lodge was developed, a new type of dwelling that enabled these people to live in more permanent villages. The floor plan of a typical lodge was a square or a rectangle. They were framed with timbers and had an extended entrance way. They were covered with a mixture of branches, grass, and mud plaster. Pits for storage of food and tools were located below lodge floors. Sites were usually located along streams or rivers, like the Missouri and Republican, where suitable garden locations were available.

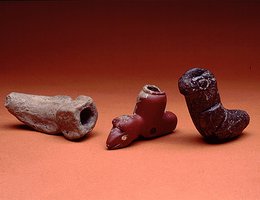

Because agriculture provided enough food to support larger populations of semi-permanent village dwellers, more artifacts from this period have been found. The artifacts from Central Plains Tradition sites were made of stone, bone, and clay. They include pipes, bone fishhooks, bone beads, a deer jawbone corn sheller, and a host of others. Artifacts include a wide variety of pottery types. Vessels were globular, with rounded bottoms and decorated only on the rim areas. Vessels were not painted and most decoration consisted of geometric patterns of lines cut into the soft paste of the rims prior to firing. Also characteristic of this period are bow and arrow projectile points that are triangular, with hafting notches on the lower edge and sometimes on the bottom.

One of the most significant investigations of Central Plains Tradition has been conducted at the Patterson site located in a valley along the Platte River and is found on either side of Highway N-31 several miles south of Interstate 80. The Patterson site is an almost 1,000-year-old Indian village and represents a typical location for people of the Central Plains tradition as it was near water and an abundant supply of timber and wildlife. Small gardens were cultivated and wood was used for house construction, fuel, and for crafting tools, and weapons.

Populations increased, societies became more complex, and the people became more dependent on agriculture — this is a pattern that was common in many regions at that time. During this same general time period (1100 - 1200 CE), the Anasazi civilization in the Southwest was at its height, as was the Cahokia civilization near present-day St. Louis. The question of which occurred first — agricultural growth or population growth — is unclear, but the two factors were obviously related.

Follow the mysterious migration of prehistoric tribes.

Around 1400 CE (600 years ago), there must have been a crisis for the Village Farmers. At that time, the number of Native American communities, and probably numbers of humans in the villages, dwindled. The territory that would become Nebraska was almost deserted for hundreds of years.

Nearly a century before Columbus’ landing, Central Plains Tradition villages were abandoned. Communities that once covered most of present-day Kansas and Nebraska plus portions of Iowa, Colorado and Wyoming moved or died. For the next 300 years, communities were confined to the Missouri River and its tributaries in extreme northeastern Nebraska and a few large villages along the Missouri in South Dakota. The plains of Nebraska were virtually unoccupied from 1400 CE until the Pawnee, Omaha, and Oto — tribes that European explorers came to know in historic times — came back into the region in the 17th and 18th centuries. For those 300 years, archaeologists lose the trail of the Central Plains Tradition culture.

Archaeologists continue to search for clues to the mystery of what happened to the prehistoric Village Farmers. Nebraska was not the only region to experience major cultural change in the 100 to 200 years prior to European contact. Complex societies, such as the Anasazi of the Southwest and Mississippians of the Midwest and Southeast, all began to crumble after 1300 CE. What caused such widespread change at that time might include a major change in the climate, overpopulation, inter-tribal warfare (over food, timber, and animals), or disease. For example, the onset of a "Little Ice Age" around 1300 C.E. may have caused environmental deterioration and helped force native inhabitants of Nebraska to move elsewhere.

What had been a successful adaptation to the environment by the Central Plains Tradition village farmers apparently failed.