Behind the scenes of this racial situation was a political machine that may have contributed to one of the most ugly incidents in Nebraska history. In the first two decades of the 20th Century, Omaha had acquired the reputation of a "wide open" city controlled by a political machine run by Tom Dennison. In 1910, one estimate put the number of prostitutes in the city at 2,500 women. Dennison was a professional gambler who had little education or social standing. To be a gambler in a city where gambling was illegal meant that he needed friends in politics and the police. Dennison bought those friendships through lavish campaign contributions and his ability to get out the vote. His base of operation was in the downtown third ward where he handed out jobs and welfare to residents in need. The third ward included the heart of Omaha’s gambling and prostitution houses. At election time, the ward could be counted on to deliver huge and lopsided vote totals for Dennison’s chosen candidate. Dennison developed a host of allies and alliances in the Omaha area, which enabled him to dominate politics in the city.

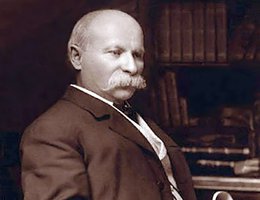

One of his most prominent allies was Edward Rosewater, the publisher of the Omaha Bee newspaper. Rosewater was a political fighter, once described as the "best practical politician in Nebraska." He knew Omaha politics as well as any other man. Rosewater was politically ambitious and wanted to exert as much influence as possible on any political decisions made in Omaha. He needed Dennison’s influence over candidates as well as his ability to deliver votes. On the other hand, Dennison needed Rosewater’s social standing and newspaper, so the two men teamed up. From at least 1897 through 1906 the alliance rode high, united behind Mayor Frank Moores who allowed the "open city" to remain open.

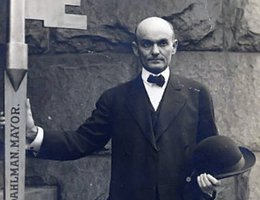

But, the political marriage between Dennison and Edward Rosewater was turbulent. Both men were Republicans, but the Republican party in Omaha also had a reform element that was caught up in the Progressive Movement. In 1906, the progressive Republicans nominated a reformer named Erastus Benson for mayor, and Dennison and Rosewater each pushed their own men. (Rosewater himself ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate that same year.) Benson won a divided primary, and Dennison was afraid that Benson would come out in favor of prohibition. In the meantime, the Democrats had nominated a popular, first-time politician named James C. ("Cowboy Jim") Dahlman. Dahlman seemed to be more tolerant of the "sporting district", so Dennison threw his support behind him. Rosewater simply couldn’t support a Democrat. Dahlman was elected and continued his close relationship with Dennison. He won eight out of nine campaigns for mayor between 1906 and 1930 — but it was the election Dahlman lost in 1918 that set the stage for racial violence.

Edward Rosewater died at the Omaha Bee building on August 30, 1906. However, Dennison continued an alliance with Edward’s son, Victor, who became the new publisher and editor of the Omaha Bee. Just after World War I, a returning soldier was hired as a cub reporter on the Bee. One day his boss told him to go talk to an Omaha businessman tied to Dennison. The reporter was told to take down whatever the businessman said and to not bother checking the facts. "Mr. Dennison is interested in this story," the reporter was told, "and it is the policy of this paper to print whatever Mr. Dennison . . . wants."

From 1908 through 1918, progressive Omahans had been pushing for reform and were slowly chipping away at Dennison’s political machine. Finally, in 1918, the reformers were able to elect Democrat Edward P. Smith as Mayor of Omaha. He was joined by a new police commissioner, J. Dean Ringer, who was determined to purify a sinful city. Smith went after Dennison’s gambling and liquor interests. Dennison and Edward’s son, Victor Rosewater were re-united and were determined to throw out the Smith/Ringer administration.

The Dennison’s political machine would do anything it could to disrupt the Smith administration, while Victor Rosewater would resort to yellow journalism to destabilize the reformers. The volatile racial situation in 1919 was the perfect issue for their purposes. Rosewater began to report allegations of black men raping white women and blamed the new reform administration for allowing lawlessness to run rampant. Dennison began to work behind the scenes to stir up violent emotions.

During 1919, Edward Rosewater’s Omaha Bee newspaper published a series of sensational stories of racial incidents that may have inflamed emotions throughout Omaha. There were lurid stories in the Bee as 21 Omaha women reported that they were assaulted from early June to late September of 1919. Twenty of the victims were white and 16 of the assailants were identified as black. Only one of the victims was black.

The World-Herald, the Daily News, and the Monitor (a black community weekly) were all very subdued in their coverage of these incidents. The Bee was not. Its coverage was a good example of what’s known as "yellow journalism" — the practice of reporting the editor’s interpretation of the news rather than objective journalism. The information reported is usually inaccurate or biased, and the language and tone is intended to arouse passions. The public has little chance to figure out the truth.

The Bee carried vivid descriptions of the arrest of blacks charged in these incidents. When police and prosecutors could not convict any of those arrested, some Omaha citizens became even more critical of the police department and the reform Smith administration. The pro-labor Mediator newspaper warned that vigilante committees would be formed if the "respectable colored population could not purge those from the Negro community who were assaulting white girls."

In early June, the Bee published an article about a young white girl in Council Bluffs who was said she was robbed, throttled, and assaulted by a black male. The World-Herald merely reported that a woman had escaped an attack by a black man.

The Bee sometimes printed editorials on the front page of the newspaper, assailing police commissioner Ringer for practicing tyranny and abuse and complained that "a ‘carnival of crime’ is being visited upon the city, with assaults, robbery, and violence the consequences of incompetent police unable to safeguard citizens."

In early September, the Bee resumed its attack on the city administration following the shooting of a young black bellboy during a police hotel raid. The paper referred to the death of the bellboy as "the ‘crowning achievement’ of the police department reflecting its ‘disgraceful and incompetent management’."

By the late summer of 1919, labor unrest, racial hatred, crime, and government ineptness fueled by a sensationalist press, had provided the ingredients for crisis in Omaha. Racial violence erupted on September 28, and before it ended, a black man would be lynched, two other people would die, the Douglas County courthouse would be in ruins, and the city would be under federal military control.