Under the reservation system, American Indians kept their citizenship in their independent tribes, but life was harder than it had been. The reservations were designed to encourage the Indians to live within clearly defined zones. The U.S. promised to provide food, goods and money and to protect them from attack by other tribes and white settlers. Also, some educators and protestant missionaries felt that forcing the Indians to live in a confined space would make it easier to "civilize the savages."

Native Indians, after 1830, found themselves being confined to reservations. But, even the Indian Territory was not safe from white settlers. In 1854, the Federal Government closed the northern half of Indian Territory and created the Kansas and Nebraska Territories. They were immediately opened up to white settlement. Many of the tribes living on the land ended up on much smaller reservations.

The reservation system was a disaster for the Indians as the government failed to keep its promises. The nomadic tribes were unable to follow the buffalo, and conflict among the tribes increased, rather than decreased, as the tribes competed with each other for fewer resources.

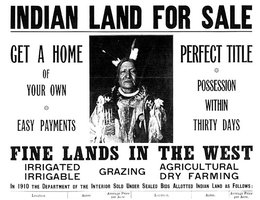

By 1871, the federal government stopped signing treaties with Native Americans and replaced the treaty system with a law giving individual Indians ownership of land that had been tribal property. This "Indian Homestead Act", official known as the Dawes Act, was a way for some Indians to become U.S. citizens.

There were two reasons why the treaty system was abandoned.

1. First, white settlers needed more and more land, and the fact that tribes were treated as separate nations with separate citizens made it more difficult to take land from them and "assimilate" them into the general population. Assimilation had become the new ideal. The goal was to absorb the tribes into the European-American culture and make Native people more like mainstream Americans.

2. Second, the House of Representatives was angry that they did not have a voice in these policies. Under the Constitution, treaties are ratified by the U.S. Senate, not the House, even though the House has to appropriate the money to pay for them. So Congress passed a compromise bill in 1871 that, in effect, brought an end to the treaty system. The bill contained the following language buried in an appropriations law for the Yankton Indians:

"PROVIDED, That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe , or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty. . ."

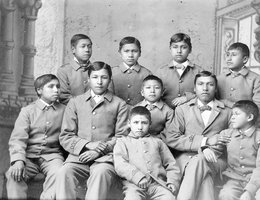

As the Dawes Act was allocating tribal lands to individuals and selling other land to whites, Sen. Dawes was also instrumental in a system of Indian schools that were consciously designed to take the Indian out of Native American children. Richard H. Pratt was a cavalry officer who spent eight years in Indian Territory commanding a unit of African American Buffalo Soldiers. He was involved with the campaign to keep Indians on their reservations and would track down hunting parties and return them to the reservation. He was appalled by the desperate conditions he saw.

Pratt’s solution was to take Indians off of the reservation and integrate them into white society through education. His intentions were probably good, although he often characterized his approach in stark terms:

"I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked . . . Kill the Indian and save the man."

He got support from Sen. Dawes and from groups of Indian reformers like the Quakers. In 1879, the federal government turned over a deserted military barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania to Pratt along with money to start his school. Pratt wasted no time in hiring a staff and teachers. Then, he traveled west to the Rosebud and Pine Ridge agencies just across the Nebraska border to convince reluctant parents to send their children halfway across the country to become white men. That first year, 82 children went to Carlisle to be educated. Some were from families who wanted the education, others were from poor families, and some were orphans who had lost their parents.

The school grew, in part because Pratt used ingenious "before and after" photographs to demonstrate his success to potential white supporters. Over 10,000 Indian children went through the Carlisle program in the 39 years it was open. Eventually, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Thomas Morgan, expanded the educational effort and built a total of 19 schools across the country. One school was built in Genoa, Nebraska.

But the schools gradually developed critics. For one thing, many of the children died at school as they were exposed to diseases for which they had no natural immunity. Few graduated during the eight available years of schooling. Many young students were so homesick that they tried to run away, despite the fact that it might be over a thousand miles back home. Punishment was harsh for those that ran or for those who could not follow a set of militaristic rules. They were punished for speaking their Native languages. There were disagreements over the kind of education that was best to teach. And despite all the punishment and intensive living experience, the children tended to maintain their sense of Indian identity. Most did not assimilate.

Finally, in 1928, the Brookings Institute was hired to study "The Problem of Indian Administration". That report criticized the poor conditions of buildings in the system, the care for students and a poor curriculum. The Hoover administration was embarrassed by the report. It increased spending on Indian education, but began to press for better schools on the reservations. It was just too expensive to ship kids halfway across the country. Throughout the 1930s, most of the Indian schools, including Carlisle and Genoa, closed.