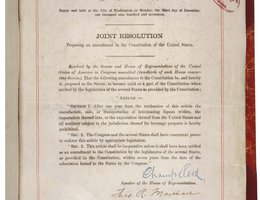

With the passage and ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919, law enforcement officials all over the nation were charged with stopping:

". . . the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States . . . for beverage purposes . . . "

Congress and the states were left with the task of figuring out how to prohibit alcohol from the public — a public that was still deeply divided about the evils of alcohol. Liquor stores and saloons were shut down. But it was not long before illegal stills were set up. "Speakeasies" sprang up, hidden saloons where you quietly whispered a password to a bouncer at the door to get in. Organized crime moved in on the illegal, but popular, trade in alcohol. And law enforcement agencies from DC to Douglas County, Nebraska, raided stills and warehouses, often at gunpoint.

President Herbert Hoover called prohibition "The Noble Experiment" and many observers seemed to agree with this assessment. "Noble" because the goals of keeping families together and reducing or eliminating alcohol abuse were noble goals. An "experiment" because most observers felt like it was an experience that failed. Too many in the country saw nothing wrong with drinking alcohol in moderation.

In fact, many people voted for the amendment thinking that it would still allow light beer and wine which had low alcohol contents. During World War I, there had been an alcohol act that allowed people to drink beer and wine but outlawed hard liquor (which has more alcohol).

After passage of the 18th Amendment, it was up to Congress to set the maximum alcoholic content in beverages. They passed the Volstead Act that was more severe than many expected. The Act put the maximum alcoholic content at 0.05 percent. By comparison, today’s beers have between 4 and 6 percent alcohol, 100 times more than the Volstead Act allowed. Whiskey had around 50 percent alcohol. So, many were shocked when the Act put the alcohol content so low. A Literary Digest poll taken in 1922 found that 40 percent of respondents favored allowing light beer and wine. The poll also found that 62 percent of working men favored lenient enforcement of prohibition.

Before the amendment, everyone from presidential candidates to song writers had been labeled as either "wet" or "dry." Historian David Kyvig, in his book Repealing National Prohibition, suggests that there was a huge group in the middle that he calls "moists." These were people who may have wanted to regulate and limit the effects of alcohol, but who did not think outright prohibition was right or enforceable.

That sentiment continued to grow as more and more speakeasies were built, as "bathtub gin" was brewed in ordinary bathrooms, and as organized crime became richer and more violent. Comedians began to ridicule prohibition. Groups of men and women began to organize. And as the Great Depression hit, people looking for work thought that legalizing breweries again might create new jobs. By 1932, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt threw his weight behind repeal of the 18th Amendment. Congress went along in 1933 and sent the issue to the states.

Nebraska was not one of the 36 states (out of 48 total, then) who voted in special constitutional conventions to ratify the repeal in 1933. However, in 1934, Nebraskans did vote to repeal the state’s constitutional prohibition by a 60 to 40 percent margin. The Noble Experiment was over.