In the later years of the nineteenth century, the number of homesteaders who mostly were farmers (also called "grangers") grew. This put pressure on the ranchers who were using large areas of public lands to graze their cattle. Not only were homesteaders taking the land, but they were taking the land with access to water, which the ranchers’ cattle needed.

This conflict between homesteaders and cattlemen was rooted deeply in two very different traditions of land use. The ranchers were mostly from the Southwest, and when they came north to Nebraska, they brought with them the Spanish idea of land use where the range was open to grazing. The farmers came to Nebraska from the east, where the model for land use was owning small farms.

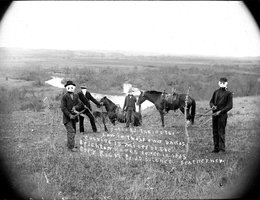

Both farmers and ranchers wanted to use public land for their own purposes. In Wyoming, these groups shot at each other, but in Nebraska, "backstabbing" was the common method. Farmers shot cattle or cut ranch fences to let cows loose. Ranchers ran cattle through farmers’ crops. It was time to bring in the law.

In other western states, the problem of grazing cattle on public lands was solved with leases. In Nebraska, the problem was solved by forcing farmers and ranchers to buy the public lands. If you wanted to ranch in Nebraska, you were supposed to own the land. The federal government accomplished this transfer of lands by cracking down on those who were illegally using public lands for grazing, and by increasing the number of acres that an individual homesteader could take.

In 1902, U.S. Congressman from Nebraska’s 6th District Moses P. Kinkaid introduced a law that enlarged a homestead from the 160 acres based on the Homestead Act. The homesteads would have 640 acres in just thirty-seven northwestern Nebraska counties. Kinkaid originally tried to get more land into the act, but Congress representatives from the crowded eastern states couldn’t understand why anyone would need so much space.

The intent of the act was to give both farmers and ranchers a better chance to be productive in the relatively dry Sandhills. Land that could be irrigated was excluded from the law, because people would pay real money for those acres. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the bill into law on April 28, 1904.

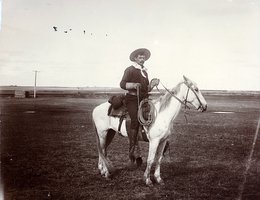

People who took homesteads under the Kinkaid Act were known as Kinkaiders, and there were quite a few of them. From the time the bill was signed until 1917, over nine million acres were distributed. That figured out to be roughly 14,000 individual claims.

It is difficult to measure the effect of the Kinkaid Act accurately. Much of Nebraska’s Sandhills region was unsuited for farming, and 640 acres was not a large enough piece of land to ranch successfully. Farmers who claimed land through the Kinkaid Act mostly failed, due to the dry dune landscape. Ranchers, however, profited by taking over land that the homesteaders abandoned.

Read more about it: