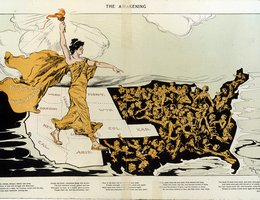

The work of the Seneca Falls Convention on women’s rights did not go unnoticed in Nebraska. From the earliest days of statehood, there was a progressive contingent that argued women should be allowed to vote since the laws representatives wrote applied to women as well as men.

So when delegates gathered in 1871 to write a new constitution for the state, votes for women was one of five proposals submitted separately to the voters. There was at least enough support to get the question on the ballot. However, when the — all male — voters in Nebraska went to the ballot box, women’s suffrage got the lowest vote total of any of the five proposals, with only 22 percent of the vote.

The issue was far from dead. Suffrage was kept alive by the efforts of people like a young Canadian immigrant, Erasmus Correll, who had moved to Hebron, Nebraska in 1869. He and his wife, Lucy, founded the Hebron Journal in 1871. They were both strong supporters of equal rights for women. Erasmus provided space in his newspaper for women who wished to make their voices heard on the issue of suffrage, and he and his wife wrote regular columns supporting feminist causes. In 1877, Correll convinced Susan B. Anthony to come to Hebron to speak on behalf of women’s rights. Two years later in 1879, Elizabeth Cady Stanton came to Hebron to lend her support to the cause.

Mr. Correll was elected to the State Legislature in 1880 and introduced a women’s suffrage bill. It was defeated, but by then over 30 local women’s suffrage organizations had been formed in Nebraska. Soon after, the Nebraska State Women’s Suffrage Association was formed. Clara Bewick Colby, of Beatrice joined the crusade and would eventually become Nebraska’s leading female crusader for women’s suffrage.

In 1882, Correll introduced another women’s suffrage bill. This time his proposal was to submit the question of women’s suffrage to the voters. Clara Colby, who made several speeches before both houses of the legislature, was credited with convincing the representatives to pass the bill. But the amendment was again defeated.

In 1891, suffragists tried again. On March 6, suffragists packed the chamber floor and galleries as a bill was debated to extend suffrage to women — not in all elections, but only in elections for municipal (city) offices. But the opponents argued that with the secret ballot, letting women vote in municipal elections would cause "untold mischief". One paper reported,

"After wasting more than two hours of time, roll call on the bill commenced. Once the bill was defeated, the legislature could get down to solid work."

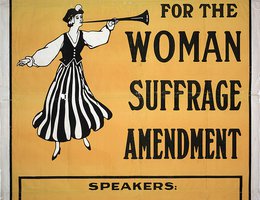

In 1914, the Nebraska Woman Suffrage Association launched an initiative campaign to place the issue on the ballot. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, President of the National Woman Suffrage Association, visited Omaha during the 1914 campaign to support the initiative. She was a confrontational and controversial personality who verbally attacked a state judge who refused to allow Nebraska women to vote for the office of superintendent of schools, even though women could vote for school board members.

Shaw’s remarks provoked an angry response from Mary Nash Crofoot, the executive board chair of the opposition association. The pamphlet was entitled, "Lest Catholic Men Be Misled". There was some religious opposition to women’s suffrage.

Although all of Nebraska’s neighbors to the north, west, and south had passed full woman suffrage before World War I, the state’s electorate rejected proposed suffrage amendments to the Nebraska constitution three times — during the 1871 constitutional vote, in 1882, and in 1914. But the proponents did not give up hope.