Settlers on the Great Plains had to contend, both physically and psychologically, with what to them was a wilderness. They faced a featureless land that many described as "a sea of grass."

Europeans and Americans brought their own way of thinking about land with them, based on a system of longitude and latitude developed in the 18th century. Property lines were drawn on pieces of paper — maps — dividing one person’s land from the next.

Native people understood the geography of the Great Plains. When settlers arrived on the Great Plains, these Europeans and Americans believed that land was something that should be owned — by individuals, businesses, or governments. They had to deal, both physically and mentally, with what to them was a wilderness. They faced a featureless land that many described as "a sea of grass."

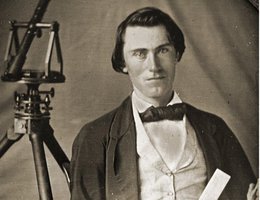

When Nebraska became a territory, its northern and southern borders were drawn mainly along lines of latitude based on a system of longitude and latitude developed in the 18th century. Surveying the territory began almost immediately, and the surveyors set markers to physically mark the imaginary lines on the landscape. Sections, townships, precincts and acreages were created — random divisions and artificial boundaries to the seemingly endless frontier. Property lines were drawn on pieces of paper — maps — dividing one person’s land from the next.

Landmarks and lines on maps told these people where they were and where their land was.

The surveys allowed the U.S. government to sell what it considered public lands to railroads, private companies, and individuals. These companies and individuals then further marked the land with roads, fences, and buildings, turning the wild sea of grasses into tame farms and ranches.

Over the years, surveyors drew more and more lines, more and more land was claimed and sold, and more and more settlers moved onto the land.