Before Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the "New World," Native Americans living in Nebraska lived in villages made up of small numbers of earth lodges, usually square in shape. Large wooden posts were placed upright in the ground and supported a framework of smaller logs. Then this was covered with grass and earth which provided shelter from the weather.

Nebraska Indian tribes, such as the Pawnee, Oto, Ponca, and Omaha, also lived in earth lodges that were round in shape and made of the same raw materials as earlier earth lodges. As many as thirty people might live in one house. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the Pawnee were living in circular earth lodges in large villages, which might include 1000 to 2000 people.

Native Americans in central and western Nebraska lived mainly in tipis. They required little wood and their hide coverings made them portable. Tribes in eastern Nebraska had more trees available and used them in earth lodges and wigwams.

Tribes using tipis could move their houses wherever and whenever they wanted. Their ponies dragged the poles that served as the framework of the tepee. Bison skins which covered the poles could be folded up and hauled by horses, too. Even the tribes which usually lived in earth lodges took advantage of this great invention. They used tipis during long journeys.

Earth lodges first appeared in the farming tribes on the plains around AD 700. At that time, the Pawnee were building earth lodge towns in what became Nebraska and Kansas. To the northeast, the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto (who were related with similar languages) built similar homes. Later those tribes would gradually move into Nebraska territory. To the far north, the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara built earth lodge villages near streams.

According to Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton in their book "Native American Architecture," all of these tribes put up their lodges in more or less the same fashion. Four or more central posts — generally cut from cottonwood trees that are plentiful on the plains — were planted in the ground and joined at the top by cross beams. A wider ring of shorter posts and beams encircled this square frame. Radiating from the central smoke hole was a wheel of roof rafters that rested on the outer ring. To complete the frame, a slanting or vertical sidewall of covering posts or split planks was placed around the basic structure to hold the earth walls. Smaller sticks overlaid with brush or grass provided a thick padding for the heavy layer of sod or loose earth, which dried like a plaster shell.

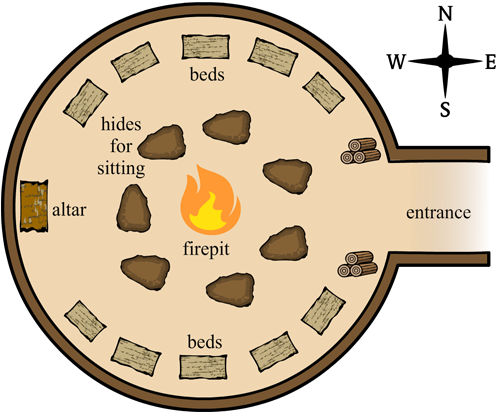

In some tribes, the earth lodge played a central role in the myths and rituals of the people. The Pawnee, for example, worshiped a host of celestial deities and incorporated astronomical symbolism in their earth lodges and the layout of their villages. Tirawa was the Pawnee’s supreme deity and creator. His domain was in the vast expanse of the sky above, so his presence in the lodge was visible through the smoke hole and the shaft of light that came through. The door was generally faced east where the morning star pours his beam into the lodge and lights the fire. On the western wall was an altar representing the evening star, the Goddess of Night. Beds were arranged around the outer walls. The fire pit was in the center.