When people are faced with frightening situations, they will take amazing precautions — even if the perceived threat never happens. People in coastal cities facing a possible hurricane will stock up on food, store water in their bathtubs and board up their windows. Just before the century changed to the year 2000, people were worried that computers around the world would shut down, bringing down power grids, ATM machines, gasoline stations, health care, transportation systems, financial and governmental services. Many took precautions.

This 1962 public service radio announcement told people what to do if they were caught outside by a nuclear attack.

This is basic civil defense information from the Department of Defense, Office of Civil Defense, Washington. If you receive warning of an enemy attack get to the nearest fallout shelter promptly. But if you’re caught in the open, and there’s a brilliant nuclear flash in the distance, take cover immediately. Even miles away you may be exposed within seconds to a searing heat wave from the explosion, followed by a blast wave and flying debris.

Get into the nearest building immediately or into a ditch or culvert, beneath a parked car, behind a tree or wall, anything solid that will give you some measure of protection. Curl up in a ball, and cover your head with your arms. Stay there until heat and blast waves have passed.

Then, go to the nearest fallout shelter before radioactive fallout starts drifting down. If there’s no fallout shelter within range, go to the nearest large building and take shelter in the basement or one of the inner hallways. Know in advance what to do in any emergency situation. Find out from your local Civil Defense office.

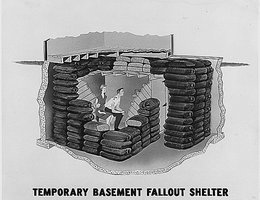

In the 50s and 60s, fears of nuclear war spurred a boom in building fallout shelters — right in your own basement or under the back yard.

A fallout shelter built in the corner of a basement was the least expensive type, and it supposedly offered "substantial protection." In many plans, concrete blocks provided the walls. An open doorway and vents near the floor provided ventilation. The shelter’s entrance was constructed with a sharp turn to reduce radiation intensity. Several Nebraska publications recommended stocking foods that would last for several months without refrigeration and that required little or no cooking. There were devices to help people know when radioativity had reached safe levels. The pocket dosimeter was a radiation detection device that included a pen-like tube that could be worn on clothing. The tube captured radioactivity in the air, and could then be read by a separate base unit to determine the level of exposure of radioactive fallout. There were even radiation detectors, known as Geiger counters available for sale.

Other plans called for construction of a separate fallout shelter several feet underground. Even four feet of earth or a couple of feet of concrete would reduce the level of gamma ray radiation that would reach the family in an underground shelter. One plan suggested the "The roof of the shelter can be used as an attractive patio." Ventilation in the shelter was provided by a hand-cranked blower attached through a pipe to a filter mechanism on the surface. By turning the crank, the shelter would be ventilated with fresh air filtered to keep out radioactive particles. National Manufacturing Company of Lincoln manufactured one popular ventilating device. Some more elaborate plans suggested installing an electrical generator to provide all the comforts of home.

Civil Defense agencies often provided red and yellow candies in their shelters that were called "carbohydrate supplements." Also, crackers known as "Nebraskits" were available. Otoe Food Products of Nebraska City canned drinking water for civil defense under its Morton House brand. Roberts Dairy from Elkhorn packaged water in the familiar milk cartons.

Sometimes, cots, sanitation kits, and tins of candy were provided by the Nebraska Civil Defense Agency for family shelters. More often, families had to buy similar products commercially.

It was recommended that people stay in the shelter full time for at least 14 days after a nuclear blast. Families with children were advised to stock their shelter with recreational materials to break the monotony. Monopoly games were popular. Other suggested items included playing cards and diaries to keep a record of one’s stay.

According to civil defense authorities, a concrete block basement shelter could be built as a do-it-yourself project for $150 to $200. Exactly how much protection they actually afforded was an open question — one that, thankfully, no one has had to test, yet.