What was it like to fly a bomber with atomic weapons on board? What was it like to know your mission was to kill thousands and even hundreds of thousands of civilians?

Much is demanded of the SAC atom-bomber crews. Their lives are something new in military history. For the first time in peacetime, SAC bomber crews were prepared to fly their missions at a moment’s notice. SAC commanders had to be constantly available; before the era of cell phones, they had to call in to headquarters to let them know what restaurant or theatre they were going to. The security at far-flung bases was tested regularly by mock surprise attacks from SAC security forces. Dwelling amid a people at peace, SAC was always on a war footing.

In 1953, Reader’s Digest followed SAC crews on a typical overnight mission.

"Their average age is 29, but theirs are not the eyes of young men. Grey hair and nervous exhaustion are common among them due to the long hours spent eight miles above the earth, shadowed by the knowledge that they handle the most terrible destructive power in the world. . . These men must maintain concert-pitch performance by incessant practice missions to the earth’s ends. There is scarcely a night when crews do not curve out to sea from their country and return to ‘strike’ some city picked for its resemblance to an actual war target. While we sleep, they fly over our homes, but too high to be seen or heard."

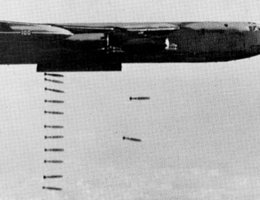

The training missions were 12 to 16 hours long, with more hours of briefing and debriefing before and after the actual flight. Flights to Russia would last that long. During that time, crews were strapped into tiny flight stations with little chance to rest or move. There would usually be at least two mid-air refueling rendezvous with tanker planes. Fighter planes would be sent up to try to intercept the bombers and end their mission. The goal of the mission, was to drop an imaginary bomb on a specific target in an American city. The targets were chosen in order to look like specific targets within Russia.

Added to the pilots’ tension was the ever-present security force that assumed Russian agents were always looking for flight information, even in Omaha, Nebraska. For example, one bomber commander had an ulcer and had to drink up to four bottles of milk a day. At one point, he was scheduled for a six-day mission to Europe. His wife canceled the milk deliveries to their house. The storeowner talked, and people in the community remarked that "Mrs. Pilot’s" husband was evidently on a long mission. SAC Headquarters heard of it. Result: a stern reprimand through channels and 24 bottles of milk were to be wasted next time.

All of this secrecy and training, of course, was designed to prepare crews to drop hydrogen bombs on Russian targets. Lt. Gen. James Edmundson, one of LeMay’s deputies, remembers feeling like he was on:

" . . . the cutting edge of the Cold War. . . . Unless we were good — if we slipped, if we were not capable of doing our job, that the Russians would eventually move in and take over. We didn’t know [whether] they’d come and outright bomb us, but there were other things that they might do that would trigger machinery in Washington which would launch SAC. . . . It was a tough life."