Most of us take road maps for granted. It is easy for today’s travelers to get a clear map to guide them on their way. This was not true with early voyagers across Nebraska’s "sea of grass." They had to make their own maps, and one of the most significant chart-making explorers was Captain John C. Fremont.

In 1841 Congress appropriate $30,000 to pay for a survey of the Oregon Trail and named Lt. John C. Fremont to head the expedition. Guided by Kit Carson and assisted with mapping by German-born cartographer Charles Preuss, Fremont conducted the first of two surveys from mid-June to mid-October of 1842. Upon his return to Washington, DC, he and his wife, Jesse Benton Fremont, prepared the official report to Congress.

Jessie was the daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton who was anxious to have the U.S. expand beyond the Great Bend in the Missouri River at Kansas City. She was bright and beautiful and instrumental in helping Fremont draft a document that soared with rhetoric and symbolism.

Fremont led five expeditions to explore the West between 1842-1853. The 1842 trip was in some ways most significant, because it outlined the Platte Valley South Pass route that would be used by most California-and Oregon-bound emigrants. Seven maps were drawn that traced the 1842 journey. Printed in 1846, the maps are based on Fremont’s field journal, as well as sketches and notes by topographer Charles Preuss.

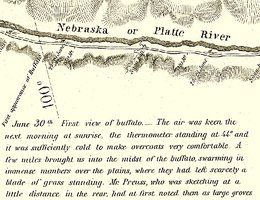

Section II of the seven-map set depicts "the Great Platte River Road" from present-day Grand Island to beyond what’s now North Platte. Even more fascinating than the thin line of river and surrounding topography, are the comments printed on the map. For example, he remarks, "Timber is extremely scarce, except on the islands. Some driftwood and buffalo excrement makes the fuel, as that of camels does in the deserts of Arabia."

Some of the excitement of encountering a new environment for the first time is conveyed in this note from Fremont’s journal, printed on the map near the 100th Meridian where present-day Cozad is located.

"June 30th. First view of buffalo. The air was keen the next morning at sunrise, the thermometer standing at 44 degrees and it was sufficiently cold to make overcoats very comfortable. A few miles brought us into the midst of the buffalo swarming in immense numbers over the plains, where they had left scarcely a blade of grass standing. Mr. Preuss, who was sketching at a little distance in the rear, had at first noted them as large groves of timber. In the sight of such a mass of life, the traveler feels a strange emotion of grandeur. We had heard from a distance a dull and confused murmuring, and when we came in view of their dark masses, there was not one among us who did not feel his heart beat quicker. It was the early part of the day when the herds are feeding, and every where they were in motion. Here and there a huge old bull was rolling in the grass and clouds of dust rose in the air from various parts of the bands, each the scene of some obstinate fight. Indians and buffalo make the poetry and life of the prairie and our camp was full of their exhilaration."

Fremont saw the great future of the West more clearly than other explorers. He saw in Nebraska the rich soil, the abundant grass and the beautiful wild flowers. To his eyes this region looked like a garden, instead of a desert, as it had been represented by many.

Nebraska probably owes its name to Fremont. In his report to the Secretary of War, he calls our great central river by its Indian name Nebraska, or Flat Water, and the Secretary of War afterwards suggested Nebraska as a good name for the new territory.

Fremont’s report became a guidebook for Americans who wanted to push westward. They did not want to read of the harsh country Pike and Long described. They wanted to learn of greener pastures. In addition, Fremont filled out the map. Lewis and Clark, Pike, and Long had only filled in a few spots. Mountain men knew specific parts of the West very well, but they were not familiar with large areas, nor were they schooled in how to describe the West in written words or cartographic terms.

While Fremont may not have been the first to explore the Platte Valley route, his 1842 travels generated the most attention. Thousands read his influential account of the explorations, studied his route west, and followed his suggestions. The maps prepared by Charles Preuss, his cartographer, served well those who followed.