There was a shortage of housing in Hastings because of the number of people who were moving there for jobs. In November, 1942, the construction company brought in about 100 Chippewa and Sioux Indians to work at the construction site.

Hidden racism in Hastings caused residents to assume that different racial groups needed separate housing. Even the local newspaper printed insults about the Sioux workers. As a result, a group of Sioux lived at the plant in tents.

Reba Yeakle recalled that Indians tended to linger around the post office building where, as a "federal people," they felt safe. Some suggested the Sioux preferred to live in camps as a separate community. But, the result was the same. The Sioux lived separately from the white community.

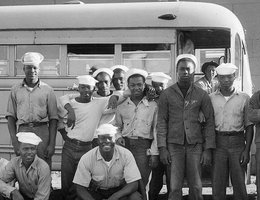

Racial prejudice became even more noticeable when the Navy announced that black sailors and civilians would serve at the Hastings ammunition depot. Immediately there was concern among the white residents about where the newcomers would live. A group of 30 homeowners from northwest Hastings went to the city council in an unsuccessful attempt to oppose the housing of blacks in the Pleasant Hills Trailer Camp near the depot. According to a spokesman for the group:

"Negro people are proud of their color. They, too, want their own communities, their own schools, their own recreation. . . . We’re proud of them and their leaders in the contributions they are making in the war effort... They too are faced with problems, being uprooted from their established homes. . . . It would be best if they could be given a community of their own."

It is doubtful if anyone asked the black families if they truly felt that way. The city council voted unanimously to oppose the housing of African Americans in the government trailer camp, even though they could not stop the government from doing so.

The federal government also provided housing for black civilian workers. When it was completed in 1944, black families lived in 260 buildings in the southeastern section farthest away from Hastings. The Hastings community had little experience with race relations, but it now had segregated housing. The segregated Navy provided segregated on-base housing as well.

"We had a lot of black boys in Hastings at the time in the military... We had not had black people [among us]. A lot of people did not like to see the black people around. They wouldn’t even sit beside them on the bus. This is just something that you grow up with. There was no reason for them not to like these people, but that’s the way it was.” — Lorena Smith, Hastings."

There was a need for recreation as well as housing, and once again, the solution was a separate location. There wasn’t much for African Americans to do in Hastings when they weren’t working. Every Friday afternoon Hastings NAD officials provided "cattle trucks" with benches on the sides, to transport black workers to Omaha where there was a larger African American community. Basically, blacks were forced to travel for hours in converted cattle trucks in search of entertainment. The white community of Hastings assumed separate facilities for African Americans were needed.

Eventually, with the help of federal money, Hastings opened a separate USO club for black servicemen. Regularly scheduled activities and dances were held.