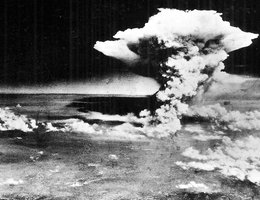

Colonel Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was airplane commander of the 509th that was responsible for dropping the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945. In 1942, Colonel Tibbets was Squadron Commander of the 340th Bomb Squadron, 97th Bombardment Group that was destined for England. Tibbets flew 25 missions in B-17s.

In March 1943, Colonel Tibbets returned to the United States to test the combat capability of Boeing’s new Super Fortress, the B-29. In September, 1944, he was briefed on the Manhattan Project, the code name for the development of the atom bomb. It was his job to organize and train a unit to deliver atomic bombs in combat operations.

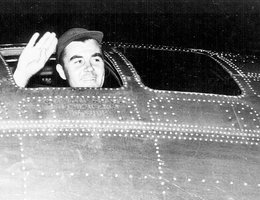

"I looked upon this airplane as one of the best B-29s ever produced. I remember picking it out of the production line at the Martin factory in Omaha with the help of a couple of foremen." — Colonel Paul Tibbets, Jr.

Nebraska, like the rest of the nation, was stunned to hear about the dropping of the world’s first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Germany, of course, had surrendered months earlier. After a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later, Nebraskans celebrated V-J Day wholeheartedly on August 15.

On September 18, 1945, the last of 531 Omaha-produced B-29s rolled out of the final assembly hall of the Martin Plant. On April 1, 1946, the Martin Company’s last 100 workers left the plant. The bomber plant was used for storage of machine tools from 1946 to 1948. Fort Crook, which was where the Martin Bomber Plant was located, was transferred to the U.S. Air Force and became Offutt Air Force Base in 1948. The Strategic Air Command Headquarters was moved to Offutt that same year.

After her mission, the Enola Gay was returned to the United States in 1946 and stored in Arizona for several years. Then Colonel Paul Tibbets, Jr. flew the plane to Park Ridge, Illinois, a storage site for the Smithsonian Institution. It made its final flight on December 2, 1953, when it was flown to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. The Enola Gay was restored and parts of the plane were put on exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum between 1995 and 1998. But there was so much disagreement over the plane’s mission that the exhibit was closed. Now, the entire restored plane is displayed at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center outside Dulles Airport in northern Virginia.

The debate over how the war was won has continued.

Visit the Smithsonian website on the Enola Gay.

"They had their chance. They started it and they had their chance, and even after we dropped the first one, they didn’t give up, so we had todrop the second one. It was a terrible, terrible thing, and it’s too bad, but there were a lot of people who got killed in that war. You’d think it would cure everybody of ever starting a war again, but it hasn’t." — Rose Marie Murphy Christensen, Columbus Grade school student.

"We knew that the cost of lives was going to be just unreal, that was the justification for it and that was the justification that we had to take too. It took two bombs to make the Japanese realize what was going to happen to them." — Mildred Pogue Gardner, Lincoln University of Nebraska student.

"I think we all agreed with him [Truman] that he made the right decision of bombing Hiroshima. If he hadn’t . . . I’m sure we would have lost an awful lot of men. They claimed that if we went into Japan, we would have lost millions. I know he saved more Americans lives than he cost the Japanese, and he probably saved Japanese lives when it comes right down to it, because they would have lost a lot more lives in the fighting than they lost in that bombing. It’s too bad they couldn’t have forgot how to make them after that bombing, but on the other hand, maybe the bombs are the things that have kept peace this long." — Tom Sherman